IUSED to blow up huge chunks of Cumbrian hillside for a living. I stopped doing it not through any regard for conservation or the environment, but because I???d noticed that none of my more senior colleagues ever reached retirement age ??? they faded away through ill health. Too many harsh winters spent in the draughty and inhospitable dampness of a quarry bottom and too much slate dust and nicotine in the lungs would wear a fella down.

IUSED to blow up huge chunks of Cumbrian hillside for a living. I stopped doing it not through any regard for conservation or the environment, but because I???d noticed that none of my more senior colleagues ever reached retirement age ??? they faded away through ill health. Too many harsh winters spent in the draughty and inhospitable dampness of a quarry bottom and too much slate dust and nicotine in the lungs would wear a fella down.

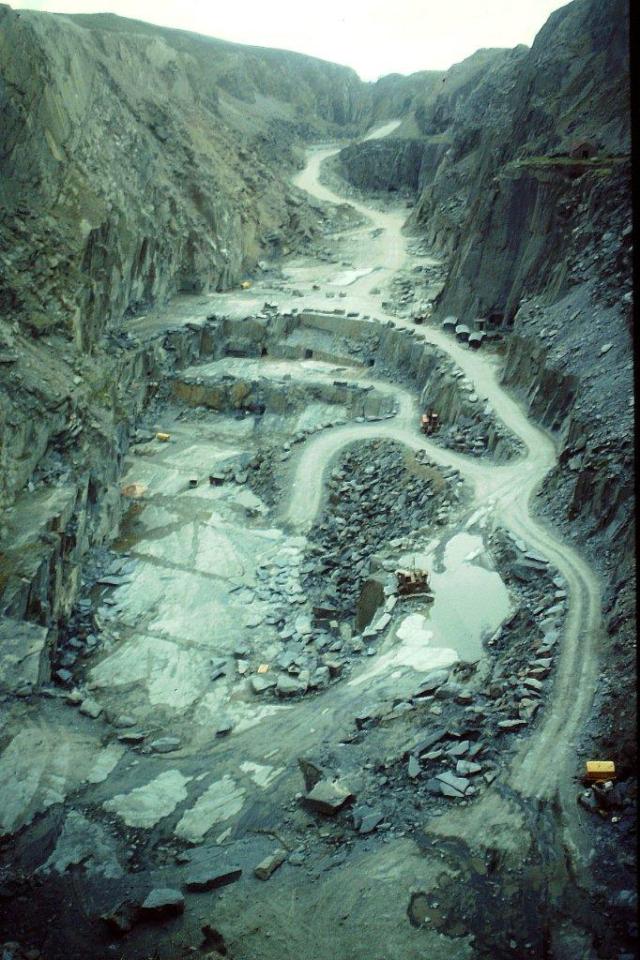

Sometimes I???d sit in the sun on the quarry top, gaze out towards the Coniston fells, the Scafell range or across the Duddon estuary to Black Combe, and consider what my industry was doing to the environment. After all, 300 years of continuous extraction on a huge industrial scale does tend to leave a mark on the landscape. Not only did my place of employment possess the largest slate quarry hole in England, but its tips covered many acres of fellside and could be seen for miles around. Some people might have considered this a blot on the landscape of significant proportion.

I didn???t. I was quite fond of the place ??? as was my mother, who worked for 17 years in the quarry offices. And a great-great-great-great-grandfather, William Mackereth ??? a tipper and weighman for 46 years before being awarded a silver snuffbox on January 1, 1866.

I considered the quarry as much an integral part of the Lake District landscape as Ashness Bridge and Castlerigg stone circle, and more so than National Trust parking meters and Hayes Garden World.

The Lake District is a national park moulded by man into something that looks natural and timeless but is the result of industry and agriculture. The native forest that once cloaked every valley and every fellside to a considerable altitude has been exploited since prehistoric times to such an extent that by the 18th Century the Furness iron industry was shipping haematite ore hundreds of miles north to Loch Etive to be smelted, timber for the local charcoal blast-furnaces being so depleted.

The Lake District is a national park moulded by man into something that looks natural and timeless but is the result of industry and agriculture. The native forest that once cloaked every valley and every fellside to a considerable altitude has been exploited since prehistoric times to such an extent that by the 18th Century the Furness iron industry was shipping haematite ore hundreds of miles north to Loch Etive to be smelted, timber for the local charcoal blast-furnaces being so depleted.

Minerals have been mined on a huge scale since the days of the Elizabethans; the fells have been shorn by sheep (at times to crisis levels) since at least monastic times; and all those quaint villages and picture-postcard towns ??? Coniston, Keswick, Ambleside, Bowness, Troutbeck, Grasmere ??? have been built from stones and slates blasted from the earth by quarrymen.

It???s in this frame of mind I???d go about my job, and it???s in this frame of mind I remain. If the Lake District was an unspoilt wilderness with a fragile ecosystem then the matter would be different. But it???s a major holiday destination where the local economy depends on 15.8 million visitors spending ??952m a year, brown heritage signs shepherd vast amounts of traffic from the motorways, and ???the official tourist board website??? gives precedence to action-packed visits to the GoApe Treetop Trek before Wordsworth???s daffodils and Rannerdale???s bluebells.

So where is this leading? This blog is supposed to be about walking, isn???t it? Yes, but it???s also about the environment and how we, as a race, have changed it and are changing it.

So where is this leading? This blog is supposed to be about walking, isn???t it? Yes, but it???s also about the environment and how we, as a race, have changed it and are changing it.

Those intriguing hollows and caverns you stumble across on the fells above Little Langdale, Torver, Seathwaite, Grasmere, Longsleddale and Kentmere ??? those deep gashes in the ground with their moss-encrusted ruins ??? their significance cannot be appreciated until the human effort that went into scratching and blasting them out for a few shillings a week is recognised.

This article is a snapshot in time. It???s an account of a heading blast that took place in December 1985 and dislodged thousands of tonnes of blue-grey slate from Kirkby Moor, and I???m recording it it here simply because it does not appear in this form anywhere else. I published a version in The Mine Explorer (the journal of the Cumbria Amenity Trust) in 1989, but this version has lots of pictures to accompany it, and that fleshes out the details considerably.

A heading blast is a means of dislodging colossal amounts of rock by driving a tunnel ??? or heading or level ??? under a quarry face, packing it full of explosives and stemming materials, and letting the whole thing go off with a bang. It is a simple and somewhat crude exercise that has been practised up and down the country for many years and with varying degrees of success ??? quite often with very little success. Hence its demise.

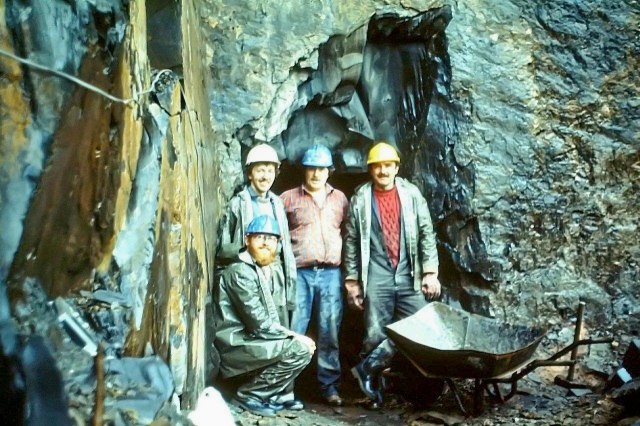

Heading blasts are now, largely, a thing of the past. They are history. They have been superseded by developments in drilling, cutting and explosives techniques. This heading blast took place in the Burlington slate quarries at Kirkby-in-Furness. The tunnel, which was 100ft long and about 5ft high, was driven during September and October 1985 by David Coward and myself using compressed-air rockdrills and ICI 80% Special Gelatine fired on No 6 detonator caps and safety fuse. All the blasted rock was removed by shovel and wheelbarrow.

The tunnel was blasted along a slipe (a vertical fault in the rock) for the first 40ft from the quarry face, then turned sharp left along a side-seam (another vertical fault running at right-angles to the slipe) for a further 60ft to take advantage of these natural weaknesses. It was an uncomfortable place, with large amounts of water streaming through the roof for most of the time. Some tunnels can be dry and dusty. This one wasn???t.

Between October and December the entire face was undercut by wire saw to ensure the slate rock, which towered 130ft above the quarry floor, would burst out cleanly when fired. Sawing is necessary to establish a plane of weakness where ??? because of the geological properties of slate ??? the rock is at its toughest.

Between October and December the entire face was undercut by wire saw to ensure the slate rock, which towered 130ft above the quarry floor, would burst out cleanly when fired. Sawing is necessary to establish a plane of weakness where ??? because of the geological properties of slate ??? the rock is at its toughest.

Wire saws were developed in the Italian marble quarries of Carrara and were first used on Cumbrian slate at Broughton Moor above Torver. Basically, a wire saw is a continuous steel loop, several hundred feet long, which is held in tension against the rock by a series of pulleys and ratchets. The moving wire drags abrasive silica-sand and water into the cut to wear away the rock. Imagine a cheese wire slicing through a lump of cheddar. That???s how the process works. Sort of. One set of pulleys takes the wire along the foot of the quarry face, the other set travels up the tunnel ??? and the rock between the two gets its feet sliced from under it.

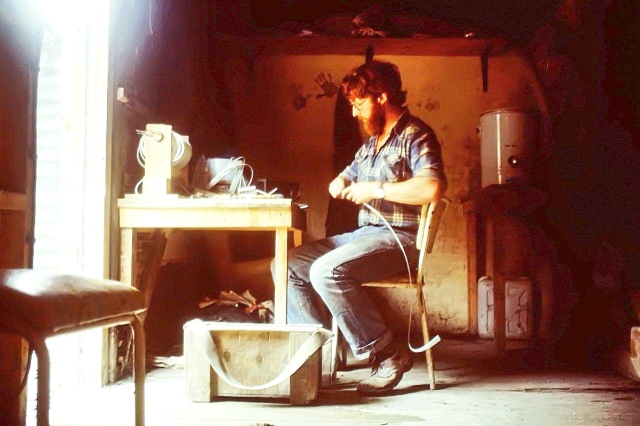

On the afternoon of Wednesday, December 11, 1985, the sawing apparatus was removed from the tunnel and the level-drivers ??? David Coward and myself ??? returned to begin blasting out three small chambers that would contain between them the 1.5 tonnes of blackpowder required to dislodge several thousand tonnes of rock. This is how events unfolded . . .

WEDNESDAY: The level-drivers arrive at the tunnel with their gear and on inspection discover that the sand deposited during the sawing operation has reduced the tunnel height to as little as 4ft in places. Copious amounts of water are percolating through the roof from the fellside above. After trouble starting the air compressor, we have time to bore only six 2ft holes to break open the first chamber. The holes are charged with dynamite (80% Special Gelatine) and fired last thing at night.

WEDNESDAY: The level-drivers arrive at the tunnel with their gear and on inspection discover that the sand deposited during the sawing operation has reduced the tunnel height to as little as 4ft in places. Copious amounts of water are percolating through the roof from the fellside above. After trouble starting the air compressor, we have time to bore only six 2ft holes to break open the first chamber. The holes are charged with dynamite (80% Special Gelatine) and fired last thing at night.

THURSDAY: Another round of holes and the first chamber is complete ??? just large enough to accommodate twenty 25kg bags of blackpowder. Mucking out the rubble from the blasting is relatively easy for the cut left by the wire saw leaves a flat floor for the shovel. Conditions, though, are cramped, there being room only to kneel while working. By evening the second chamber is well under way.

FRIDAY: The second chamber has been finished. All the muck and rubble from blasting has been thrown back into the tunnel and forms a sizable obstacle over which we are obliged to crawl. By evening, the third and final chamber is almost complete. Here, too, there is a heap of rubble almost blocking the tunnel.

SATURDAY: The level-drivers are aided by two quarrymen. The first chamber is cleared until it is spotless and ready for the powder. The muck is almost blocking the tunnel but we make enough room to allow a wheelbarrow to be dragged through. The third chamber is finished with a final round of holes. We then blast recesses just inside the tunnel entrance ??? where lengths of railway line will be inserted to hold in the stemming material when the tunnel has been backfilled.

SUNDAY: Twenty bags of blackpowder are packed in the first chamber, which has been lined with planks and two layers of heavy-duty polythene sheeting to protect the explosives from water. A bundle of dynamite on a doubled length of Cordtex detonating fuse is packed among the bags and run out into the quarry in alkathene piping. Then we start walling in the explosives. Barrowloads of walling stone are dragged along the tunnel and this is packed right up to the roof by the level-drivers. By evening the tunnel has been totally backfilled as far as the middle chamber.

SUNDAY: Twenty bags of blackpowder are packed in the first chamber, which has been lined with planks and two layers of heavy-duty polythene sheeting to protect the explosives from water. A bundle of dynamite on a doubled length of Cordtex detonating fuse is packed among the bags and run out into the quarry in alkathene piping. Then we start walling in the explosives. Barrowloads of walling stone are dragged along the tunnel and this is packed right up to the roof by the level-drivers. By evening the tunnel has been totally backfilled as far as the middle chamber.

MONDAY: More powder arrives by Land-Rover. The second chamber is charged and linked into the Cordtex detonating fuse. The team is made up to five with the addition of another quarryman whose task is to ???knock up??? large blocks of stone with a tulley ??? a heavy hammer with an axe-like edge ??? to render the walling material small enough to be handled underground by men working on their knees. By evening the tunnel has been stemmed to within 4ft of the third chamber.

MONDAY: More powder arrives by Land-Rover. The second chamber is charged and linked into the Cordtex detonating fuse. The team is made up to five with the addition of another quarryman whose task is to ???knock up??? large blocks of stone with a tulley ??? a heavy hammer with an axe-like edge ??? to render the walling material small enough to be handled underground by men working on their knees. By evening the tunnel has been stemmed to within 4ft of the third chamber.

TUESDAY: The level is soon walled up to the third chamber ??? but there is no powder left in the quarry magazine. The team members rest in the cabin while rain hammers on the roof and Christmas draws near. By mid-afternoon there is still no powder so the level-drivers decide to wall up the sides of the entrance tunnel, leaving barely enough room for the wheelbarrow to pass. Powder arrives at 2.30pm from one of the quarries up in the fells (Bursting Stone, Elterwater, Broughton Moor, I forget which one) and by evening the third chamber has been charged and securely walled in.

WEDNESDAY: The level-drivers are now stemming the wettest part of the tunnel and oilskin suits fail to repel the incessant water (down the neck, up the arms, it gets in everywhere). By lunchtime, stemming has progressed around the corner. The iron rails, dug from an old tramway, are in position by evening ??? a final buffer to prevent all the stone blowing out when the explosives are detonated.

WEDNESDAY: The level-drivers are now stemming the wettest part of the tunnel and oilskin suits fail to repel the incessant water (down the neck, up the arms, it gets in everywhere). By lunchtime, stemming has progressed around the corner. The iron rails, dug from an old tramway, are in position by evening ??? a final buffer to prevent all the stone blowing out when the explosives are detonated.

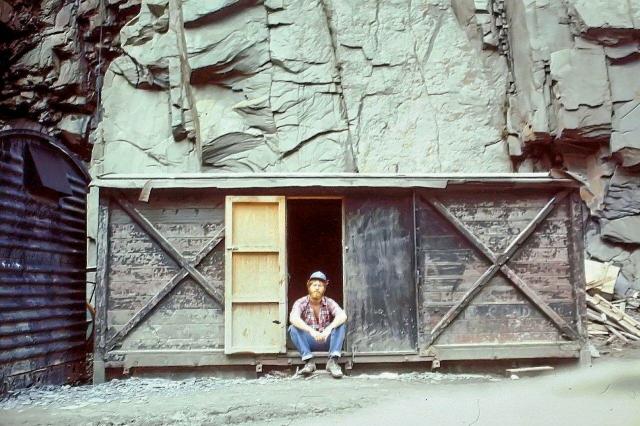

THURSDAY: A final few feet of stones are added to strengthen the rails, and the job is complete by 11am. The level-drivers clear their gear from the area. At 1.10pm the company directors assemble at a safe distance on the top of the Rightway, the north-western wall of the quarry, to view the heading blast. The level-drivers prepare a length of safety fuse with a No 6 cap and wait for the dumpers and face-shovels to leave the quarry bottom. At 1.15pm the mist comes down and fills the quarry. No one can see a hand in front of his face. The level-drivers light the fuse, which is taped to the Cordtex, and retire to safety. Two minutes later there???s a tremendous roar as countless thousands of tonnes of rock crash to the quarry floor, unseen in a Cumbrian mist.

These pictures show an explosion because they were taken on a subsequent occasion. I played a part in six or seven heading blasts at Kirkby. Most were successful, but on one instance water got into a chamber during the walling operation and ruined the blackpowder, resulting in a blast that left slabs of rock towering precariously above the quarry floor. Another time, just when the wire sawing was nearing completion, the quarry face began to move under its own weight and chased everyone out.

These pictures show an explosion because they were taken on a subsequent occasion. I played a part in six or seven heading blasts at Kirkby. Most were successful, but on one instance water got into a chamber during the walling operation and ruined the blackpowder, resulting in a blast that left slabs of rock towering precariously above the quarry floor. Another time, just when the wire sawing was nearing completion, the quarry face began to move under its own weight and chased everyone out.

Surveying the results of the blast, from left, wire sawmen John “La’l Joker” Postlethwaite and Ronnie Cartmel, quarrymen Peter Inman and Chris Cook, level-driver David Coward and quarry manager Mike Dickinson

The next morning, David Coward up on the “hill”, the mound of blasted rock that now fills the end of the quarry

I once worked with an old quarryman, Jim Allonby, who as a young man had been a level-driver in Goldmire Quarry, near the railway line into Barrow. One heading blast he witnessed didn???t dislodge a single rock. Instead, the explosives blew all the stemming material out of the tunnel in the direction of a passing munitions train. A similar duff blast once occurred at Kirkby, the old lads told me, when the tunnel???s contents were disgorged like cannon balls and the powder ???roared fa lang enuff???.

If this all sounds a bit haphazard it???s because it is. That???s how we???ve evolved. And that???s why the Lake District is at it is. That???s why you can climb Yew Crag and find the back of a lorry and a bedstead halfway up the fellside, a ship???s steam winch on Coniston Old Man (and another inside the mountain, if I remember correctly), a pile of Welsh slate miles from anywhere in the Calbeck fells, and the parallel universe that is Hayes Garden World in Ambleside. Until recently there was a blacksmith???s anvil in Brown Cove, not far beneath the summit of Helvellyn. But someone???s spirited it away. Have you ever tried to lift a blacksmith???s anvil? Don???t.

And finally, the GoApe Treetop Trek. An old friend of mine, Cockney Harry, was treated to a day out here for his 60th birthday. Apparently it???s a right good do.

Superb post and photos. I have a bit of a fascination with quarries, having grown up in a town dominated by one. Like many, it now lies dormant, with abandoned machinery dotted around. I think those who profit from the quarrying should also be responsible to the site cleanup afterward, despite the enjoyment I get wandering such sites photographing the detritus.

Hi Fraser. Yes, I must agree with you there. I think that nowadays there are safeguards in place for landscaping and such like when planning permission is granted. It’s not like the old days when they just walked away and left everything.

Cheers, Alen

fascinating historical insight.

Thank you very much for that, AnneB. Nice to hear from you again.

Cheers, Alen

It’s an exciting story, you have been involved in on your old workplace. I don’t think you will ever forget that kind of job due to weather impacts, the explosions and the collaboration with colleagues. It seems to be the kind of dangerous work where things quickly can go wrong if you are not careful. Great stuff!

Hanna

PS I have greetings from Rico, Madagascar

KABOOM!!!

Hanna, you always make me laugh. Rico indeed! Ha ha.

Cheers now, Alen

Alan

Ive been waiting all day to read this post since your RSS feed emailed me.Your old mining days accounts are what first got me attracted to Because they’re there in the first place, absolutely fascinating by all accounts with pictures to boot. will read again later & share.

Cheers,

Hi Paul. Thanks very much for that. It’s gratifying to know that people are interested. It did cross my mind that some might just move on when they realised it wasn’t strictly about walking. But hey, it makes it all worthwhile if they can take something from it. So thanks again.

Cheers, Alen

I really enjoyed that Alen. It is interesting to see the size of the workings and how they are created, especially so considering that in some places such as Honister most of it is actually underground. You certainly did right getting out of the job. I don’t think many people recognise just how damaging some types of manual work can be on your health. I certainly wish I had not waited until my health suffered before changing careers that’s for sure.

Hi David. It’s funny, sometimes I miss that sort of work and the banter between colleagues. But the cold, the damp and the dusty conditions aren’t good for the health and have a detrimental effect in more ways than one. Joints suffer, lungs suffer. Then there’s vibration white finger and other ailments ??? not to mention the physical danger aspect. Still, at least we’re in one piece.

Cheers, Alen

Thanks for that Alen, another interesting and educational post. My dad was a coal miner and I used to love his tales from “dahn pit”. The only disadvantage of having an expert in the family was that if we were watching a tv drama that happened to be set in a coal mine my dad would chunter on at the telly saying “it were nowt like that”. Like you he got out when he could and such was his superstition he didn’t even go back down to get his tools.

Hi Karl. That’s a good tale. I suppose in leaving his tools he was cutting his links once and for all. Jobs like that were commonplace and taken for granted not too long ago, and now they’ve practically disappeared. My Scottish ancestors were coal miners just north of Dumfries ??? and that’s something I really should look into.

Cheers, Alen

Fantastic memories and photos, Alen. You probably did well to get out of that occupation for the sake of your health, though. Those pics of the tunnels ready primed with explosive are a bit scary! You remember it all in such detail – did you keep a diary at the time?

Hi Jo. Thanks for that. Yes, I kept a very detailed diary and I’m glad I did because I would have forgotten everything. One of the reasons I started this blog was because I found that once I’d stopped writing things down ??? about 1987 ??? black holes began to appear in my memory. Probably an age thing. So I’ve about 15 years worth of mountain walking that are more than a little bit vague. Carry on blogging, that’s my advice. It’s more fun than writing a diary and you meet new people.

Cheers, Alen

Don’t apologise for digressions, this was fascinating!

Hi Mrs Potter. Thanks very much for that.

Cheers, Alen

Speechless. I could write an article about all that I enjoyed on this trip. Read it three times now and still can’t find the words other than it reminds me of my old railroad days in the Rocky Mountains. Thanks amigo.

Hey, thanks for that, Dohn. I think an article about your railroad days in the Rocky Mountains would be right up my street. Put it on your list of things to do.

Cheers, Alen

Loved the technical info Alen. I wish I’d asked my dad more about Shap Granite. I do know that the grey patches found in the middle of the granite were called heathens. Love the bushy beard.

I came across some references to heading blasts at Shap when I was researching this, Greg. In the blue quarry and the pink quarry. That’s interesting about the heathens ??? I’ve not heard that word before. And the beard’s a lot neater these days, and somewhat greyer it must be said.

Cheers, Alen

Thanks for the like on my blog. Quarrying’s never held any focussed interest for me before, but this was fascinating. Passing by the old mines, following the routes the miners themselves walked, I’ve always admired them, but this is a different level. I’ll be back.

Martin

Hi Martin. Thanks very much for that.

Alen

Not sure how I missed that – very interesting stuff. We live opposite a quarry and we used to be sat on the sofa sometimes and suddenly the whole house would shake a couple of times. That was then followed by the sound of the blast from the quarry – back in around the 70s, they used to rock the whole village when they blasted! Another time we went up the woods opposite the quarry face (across a road and probably a couple of hundred yards distant) and found it was littered by fallen trees and huge boulders – glad I wasn’t having a stroll there at the time!

Carol.

Hi Carol. Wow. That sounds like a whole load of great entertainment and completely free as well. Do you wear hard hats when you’re sitting on your sofa?

We once had a house that was next to a knackers yard, but that wasn’t so much exciting as smelly. And one summer we had to get the council out when there was an explosion in the rat population. That was mildly entertaining though somewhat worrying.

Cheers, Alen

Ooh – I wouldn’t have wanted to be next to a knacker’s yard. The smell must have been horrific and I love animals so would have been upset daily.

The quarry doesn’t blast like that any more. They still blast but nothing which rocks the village. That’s progress I guess… It was interesting reading what goes on in quarrying though on your post.

Just found this post…utterly fascinating. I love quarries and mines and find them beautiful, if poignant places. I feel you have summed up my thoughts exactly in this post, and I loved your description of a twee garden centre as in a “parallel world”. Thanks for such an entertaining read.

cheers,

Iain

Hi Iain. Thanks very much for that. Positive feedback keeps me going and fuels me up for something else. Glad you liked the garden centre comment.

Cheers, Alen