BETWEEN Reeth and Tan Hill lies a land of strange names. It???s a country where wild open moors and grassy dales are neatly partitioned by walls built seemingly randomly, and generations of people have drifted through in search of shelter or sustenance. Romans mined lead here; Vikings settled; industry came and went in an almost forgotten belch of furnace fumes. All left their scars and moulded this peaceful green valley known as Arkengarthdale . . .

In this land of strange names I park the van on a hill above a village called Whaw. I???ve never pronounced this name in conversation, but I???m assuming that if spoken with authority it would halt a running horse. I might be wrong.

Whaw is of Viking origin. According to Wikipedia, the Vikings who settled in Arkengarthdale came from the east, which suggests they were Danish. Norwegian Vikings migrated mainly from the west, having sojourned for a generation or two in Ireland before moving on. This was all before freedom of movement between European countries became enshrined in law. (Click images for high-res versions)

Here???s a few more strange names: Faggergill; Sloat Hole; Ovening Nick; Blacksike Foot; The Howl; Scabba Wath; Adjustment Bottom; Malice End; Charity Pasture; Ling Pulled Hill; Mudbeck Head and Fryingpan Stone.

Here???s a few more strange names: Faggergill; Sloat Hole; Ovening Nick; Blacksike Foot; The Howl; Scabba Wath; Adjustment Bottom; Malice End; Charity Pasture; Ling Pulled Hill; Mudbeck Head and Fryingpan Stone.

I leave the van near Whaw Gill Bridge and wander down the hill into the village. I have no plan for today, merely a loose collection of ideas associated with this wealth of strange names.

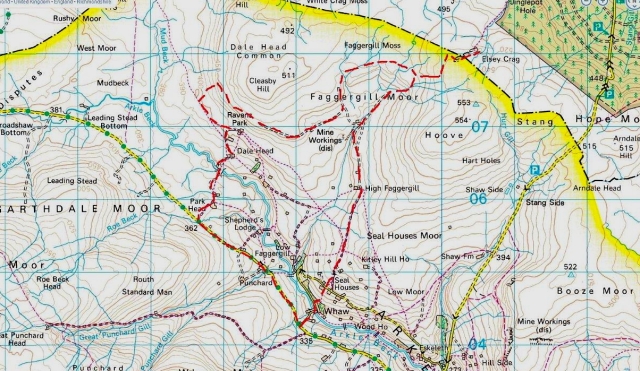

Last night, while poring over a virtual map, I chanced upon the Fryingpan Stone, which stands on the border between North Yorkshire and County Durham on the very top of Elsey Crag. I could find no additional information about the stone ??? not a single reference, historical, geological, anecdotal or mythological. So naturally I feel drawn to it ??? not so much as a moth is to a flame, more like a hungry man to a frying pan.

Whaw is a nice place because the cottages look lived-in as opposed to visited occasionally. Windowsills are slightly cluttered and curtains are functional.?? There are proper clothes pegged on washing lines, and propane bottles aren???t hidden from view. I just know that those kitchens are warm and smell of last night???s wood smoke. Don???t ask me how I know this. I guess it???s a gift.

Whaw is a nice place because the cottages look lived-in as opposed to visited occasionally. Windowsills are slightly cluttered and curtains are functional.?? There are proper clothes pegged on washing lines, and propane bottles aren???t hidden from view. I just know that those kitchens are warm and smell of last night???s wood smoke. Don???t ask me how I know this. I guess it???s a gift.

My path takes me up a steep bank through pasture fields and narrow stiles to a moorland track that passes High Faggergill Farm to the spoil heaps of the long-abandoned Faggergill Mine. At this point we step back in time to an episode in 1870 which upset a great many people and changed their lives for ever.

My path takes me up a steep bank through pasture fields and narrow stiles to a moorland track that passes High Faggergill Farm to the spoil heaps of the long-abandoned Faggergill Mine. At this point we step back in time to an episode in 1870 which upset a great many people and changed their lives for ever.

Faggergill Mine was a large and productive producer of a silvery mineral known as galena ??? a sulphide of lead. But by the 1870s the Pennine lead mining industry was struggling to maintain profits, with production falling rapidly. Faggergill, with its extensive workings and about fifteen miles of tunnels, was taken over by a new company in 1870 ??? and one of the first actions of the management was to impose strict working hours over a five-day week and take punitive measures against miners who turned up late for a 7am start. The miners reacted by walking out on strike.

Faggergill Mine was a large and productive producer of a silvery mineral known as galena ??? a sulphide of lead. But by the 1870s the Pennine lead mining industry was struggling to maintain profits, with production falling rapidly. Faggergill, with its extensive workings and about fifteen miles of tunnels, was taken over by a new company in 1870 ??? and one of the first actions of the management was to impose strict working hours over a five-day week and take punitive measures against miners who turned up late for a 7am start. The miners reacted by walking out on strike.

It would be easy for people like us, sitting in front of our laptops with the central heating warming our homes and Bargain Hunt on in the background, to make an immediate judgement and condemn the Faggergill miners for their reluctance to get out of bed in a morning and contribute to the wellbeing of their dying industry.

It would be easy for people like us, sitting in front of our laptops with the central heating warming our homes and Bargain Hunt on in the background, to make an immediate judgement and condemn the Faggergill miners for their reluctance to get out of bed in a morning and contribute to the wellbeing of their dying industry.

But 19th Century lead miners weren’t paid an hourly rate or a salary for a 37-hour week like the rest of us. They were paid for the amount of ore they produced during an agreed period of weeks or months, and regarded themselves not as employees but sub-contractors with a degree of autonomy. Tunnellers and shaft-sinkers were paid by the fathom (6ft or 1.8m) for the ground they penetrated, not the time spent labouring. Strict working hours were, to a very large extent, immaterial. Worse, they had a detrimental impact on the miners’ vital secondary source of income, which came from subsistence farming and smallholdings. The result was a very rare and extremely bitter dispute which lasted eight weeks.

The strike had devastating consequences. After eight weeks the miners, greatly depleted in number, were starved back to work. The Darlington and Stockton Times, the main newspaper in the area, reported that as many as fifty families fled Arkengarthdale in search of alternative employment, so dire was their plight.

Faggergill Mine produced handsome profits until 1887 before sinking into a steady decline, finally closing under different ownership in 1914.

There’s an old mine shop, or bothy, at Faggergill which has been converted into a hut for the grouse-shooting fraternity. Unlike many shooters??? bothies, this one remains unlocked for the use of walkers ??? an appreciated gesture. It’s a cosy place to sit for a while, eat a sandwich, and reflect on history.

There’s an old mine shop, or bothy, at Faggergill which has been converted into a hut for the grouse-shooting fraternity. Unlike many shooters??? bothies, this one remains unlocked for the use of walkers ??? an appreciated gesture. It’s a cosy place to sit for a while, eat a sandwich, and reflect on history.

Arkengarthdale today is a pleasant and picturesque valley where sheep bleat and tractors chug along narrow lanes. A hundred and forty years ago it was wracked by industrial unrest and deprivation. It’s easy to forget stuff like this and assume that the present and the past are one homogenous and unchanging mass. But they are different worlds. Yesterday’s harsh and inequitable world has disappeared without trace from our modern perceptions.

The humble Belfast sink is one of Britain’s most enduring inventions. I wouldn’t be without one ??? as you can see

I wander on past partially collapsed mine entrances to the top of Faggergill Scar and across bogland to Elsey Crag, which stands prominently on the skyline. The Fryingpan Stone is immediately obvious. It is the uppermost of a pile of boulders and has a large depression ??? the shape and size of a large frying pan, no less ??? carved into its surface.

I have noticed that many of the surrounding boulders on the crest of the crag also have depressions on their upper surfaces. Is this the result of water and weather acting on the native limestone over thousands of years ??? or is this the work of man? The land to the immediate north and east of Elsey Crag is noted for its Bronze Age cup and ring carvings. Barningham Moor, with its carved panels and rock art, is only a mile or so distant. Yet I can find no reference to these peculiar depressions on Elsey Crag, nor any reference to the origins of the Fryingpan Stone carving.

I have noticed that many of the surrounding boulders on the crest of the crag also have depressions on their upper surfaces. Is this the result of water and weather acting on the native limestone over thousands of years ??? or is this the work of man? The land to the immediate north and east of Elsey Crag is noted for its Bronze Age cup and ring carvings. Barningham Moor, with its carved panels and rock art, is only a mile or so distant. Yet I can find no reference to these peculiar depressions on Elsey Crag, nor any reference to the origins of the Fryingpan Stone carving.

The OS map also shows another peculiar feature, the Kettle Stone, standing at the north-east end of Elsey Crag. Off I whistle to track it down in the bog and heather, working on the principle that if the Fryingpan Stone has a frying pan carved on it, the Kettle Stone will have a kettle.

The OS map also shows another peculiar feature, the Kettle Stone, standing at the north-east end of Elsey Crag. Off I whistle to track it down in the bog and heather, working on the principle that if the Fryingpan Stone has a frying pan carved on it, the Kettle Stone will have a kettle.

Logic, unfortunately, does not prevail and the search for the kettle goes cold. In fact, it runs out of steam. I do, though, manage to locate a fascinating boulder, lying in the bed of a spring, in the centre of which is a deep and impressive bowl.

Some of these bowls must surely be Bronze Age rock art associated with the cup and ring carvings beneath Elsey Crag on Scargill Low Moor and its immediate neighbour, Barningham Moor. Can anyone shed any light on them, or the whereabouts of the Kettle Stone? (I’ve contacted David Forster of Bluestone Images, the man responsible for firing up my interest in Bronze Age carvings, but his search for the Kettle Stone in 2007 proved unsuccessful as well)

Some of these bowls must surely be Bronze Age rock art associated with the cup and ring carvings beneath Elsey Crag on Scargill Low Moor and its immediate neighbour, Barningham Moor. Can anyone shed any light on them, or the whereabouts of the Kettle Stone? (I’ve contacted David Forster of Bluestone Images, the man responsible for firing up my interest in Bronze Age carvings, but his search for the Kettle Stone in 2007 proved unsuccessful as well)

The afternoon is wearing on. With the hunt for the Kettle Stone going off the boil and now on the back-burner, I return through the unfriendly boglands to Faggergill Scar and follow its crest around the valley to a track that cuts along the higher slopes of Arkengarthdale.

The afternoon is wearing on. With the hunt for the Kettle Stone going off the boil and now on the back-burner, I return through the unfriendly boglands to Faggergill Scar and follow its crest around the valley to a track that cuts along the higher slopes of Arkengarthdale.

One of my loose ideas was to continue my walk on the southern side of the Tan Hill road and make my return over Arkengarthdale Moor and down Great Puchard Gill, but I have left it too late. However, there are compensations.

Even on this wild and little-frequented track there are reminders of our past and how we wrestled with the environment. Tiny crystals glint in the afternoon sunshine among the stones and mud. Many are worthless shards of calcite and quartz which have been shovelled from the mine dumps and used as a surface material. But also in evidence is the unmistakable steely blue-black glint of galena ??? the ore of lead which has been hacked from these hills since Roman times.

I plod through three farmyards and along a mile of road as rain clouds gather and the sun falls behind the hills. In this valley where Romans toiled, Vikings settled, furnaces belched, disputes raged and hunger forced families to flee, yellow lights flicker in windows and smoke rises from chimneys. Another ordinary day is over in Arkengarthdale.

I plod through three farmyards and along a mile of road as rain clouds gather and the sun falls behind the hills. In this valley where Romans toiled, Vikings settled, furnaces belched, disputes raged and hunger forced families to flee, yellow lights flicker in windows and smoke rises from chimneys. Another ordinary day is over in Arkengarthdale.

AND FINALLY: Old Railway Wagon Number 17 . . .

AND FINALLY: Old Railway Wagon Number 17 . . .

DECOMPOSING on the moors beneath the track to High Faggergill Farm, this old railway goods wagon will clatter no more along life’s iron rails. It is recorded here simply because it will almost certainly not be recorded anywhere else or with such reverence.

The only evidence of the Romans in Arkengarthdale was the discovery of a lead ingot stamped with the name Hadrian, but this has since disappeared. The only evidence of the Vikings is in the place names they left. The only evidence of the miners is the scars on the landscape and bone-dry legal documents and tonnage records locked away in archives. So let the rust and rotten struts of this once-noble wagon be recorded here for the world to admire.

NOTES ON THE FAGGERGILL STRIKE OF 1870

NOTES ON THE FAGGERGILL STRIKE OF 1870

EPISODES such as the Faggergill strike were few and far between in the Pennine ore fields. There is mention of the strike in one brief sentence on the Wikipedia page for Arkengarthdale, but my main source of reference for this post was a Durham University thesis by Colin George Flynn titled The decline and end of the lead mining industry in the northern Pennines 1865 ??? 1914: a socio-economic comparison between Wensleydale, Swaledale and Teesdale. The thesis is a wealth of information for anyone interested in the history and development of Pennine lead mining and can be accessed or downloaded in PDF form here.

Flynn goes into great detail on how the miners were paid per “bing” of ore produced or fathom of ground driven, and how they were encouraged by the mining company to farm smallholdings on company land ??? in their spare time, naturally ??? in order to keep wages down. The miners were also obliged to hire or purchase equipment from the company (candles, shovels, picks, explosives), the cost being deducted from their pay. It was a hard existence and poverty was rife. Higher wages in the iron mines of Furness and Cleveland, and in the collieries of Lancashire, Yorkshire and Durham, tempted many away. It’s not hard to see why.

Another ‘Gud Un’, funny the footpath comes down Black Gutter and stops at the lost Kettle stone but doesn’t carry on to the Fryingpan stone ? cheers Danny

LikeLike

Hi Danny. I hadn’t noticed that. Why would a public footpath end in the middle of nowhere? Perhaps it’s to do with the county boundary and the practices of different local authorities.

Cheers, Alen

LikeLike

Another interesting post from an area I don’t go to. I particularly liked your post about the houses in the Dales village where people were actually living in the houses instead of visiting. If there was a lot more of that, I don’t believe we’d have the ‘severe housing shortage’ we apparently now have!

I’m enjoying the ‘old railway wagon’ series ????

Carol.

LikeLike

Hiya Carol. I’ve driven past Whaw loads of times and cycled past three times, but I’ve never actually visited the village before because it lies on a cul-de-sac just off the Tan Hill road. It’s a really nice place. There are a couple more similar villages in that area so I should take a walk through them one of these days.

Cheers, Alen

LikeLike

I’m not even sure I’ve been to Arkengarthdale – shameful isn’t it, considering where I live

LikeLike

Put it on yer list. You won’t need your climbing gear.

LikeLike

It’s a long list just now!

LikeLike

Talking of interesting names, I went all the way to Crackpot hoping there’d be a pointy roadsign I could stand next to. There wasn’t, and the joke escaped. I’m always trying to figure out unusual place names; not just hills, but roads too.

And you found another railway carriage. You must have enough photos now for a game of Top Trumps.

Chris

LikeLike

Hi Chris. I’ve enough railway wagons for a decent train set. That’s probably why I like photographing them ??? because when I was 11 we moved house and there wasn’t enough room in the new one for our big train set, so my parents sold it on the sly without telling us. Talk about being scarred for life.

I’ve never been to Crackpot but I’ve seen it there on the map near Reeth. What a great place to have in your address.

Cheers, Alen

LikeLike

They sold the train set on the sly! That’s up there with serving the pet rabbit at tea time or moving house while you’re at school.

LikeLike

Chris, that hasn’t made me feel any better.

LikeLike

You have reminded me with this post that I have unfinished business up there as far as finding the Kettle Stone, as it may be a case of the name not being quite in the right spot on the map. For example the Frying Pan Stone is located at the end of the words “Frying Pan Stone” on the map and when I looked for the Kettle Stone I looked in the area of the footpath end rather than any further east if you get what I mean. On the other hand it may have been moved like the Roman Shrines to the north were.

LikeLike

Hi David. Your Roman Shrine story made me laugh. I see they’re still marked on the OS maps on the internet, despite the fact they have been removed. You should consider suing the OS under the Trades Descriptions Act.

I had a quick look round the area where the Kettle Stone is marked but drew a blank. I might have a wander up there some time from the Scargill side. It’s an interesting area.

Cheers, Alen

LikeLike

Wow, Alen! I don’t know where to start. With the stones, I think – I am intrigued and delighted by those little cup-shaped hollows! How on earth???? Especially, I love the cute little one that you found while looking for the kettle stone. I would most definitely have made you carry this one back down the hill! And I love all the place names – and the mining history – and the bothy – and the little samples of galena that you found. What a sad story about Faggergill Mine. The closure seems almost divine justice, after such harsh treatment of the workers. What would you do with the roller, by the way?!

LikeLike

Hiya Jo. Those stones would make nice garden features so I might go back with a trailer and bring some home and use them like those strawberry planters you buy at B&Q. And the roller would be useful for keeping the garden tidy. I might take up crown-green bowling when I’m older.

On a more serious note, the mining history of the area is fascinating, more so because most of it has disappeared, so any scraps of information that survive are all the more valuable.

All the best, Alen

LikeLike

Hi Alen, I have been enjoying your wondrous blogs for a couple or so years now, this is my first reply/comment! Great photo’s and inspiring poetic writing.

I have spent a lot of time wandering around the ‘Dales, in the same kind of places you have, often alone and enjoying the solitude. Your blogs bring the memories back and more besides.

I recognise your name from CAT in the ’80’s, I used to frequent the same kind of places, though mostly in the Pennines. These days I prefer the fresh air and sunshine – it’s much nicer!

Cheers, Mike W

LikeLike

Hi Mike. Thanks for that. I used to do a lot of pottering about with CAT in the Dales during the 1980s but we spent a lot of time looking for places and not actually finding them. Still, they were great days and I wouldn’t have changed any of it.

I often find, as I did the other day in Arkengarthdale, that I am re-learning stuff I had once known and since forgotten. Still, it’s an enlightening process in one way or another.

Cheers, Alen

LikeLike

By the way, about the hollows in the rock – some are doubtless man-made, or enlarged by the hand of (ancient) man, but a lot of the twisty runnels on the gritstone edges I think are natural. I’ve noticed them quite often when I’ve been rock-climbing. My thinking is that birds have for millennia been pooing on these edges, upon which they often perch. The acidic? droppings leach into the rock and cause some corrosion, and wind, rain etc. does the rest. In some places I’ve seen these runnels over a foot deep, and extending for several yards – on gritstone! Where the edges are still used as bird-perches there is usually a lot of green algae about. Birds of prey and crows and suchlike use them.

(Got my monika right this time – wandered over from volcanocafe, which I recently ‘joined’, and made exactly the same mistake on my first post there. Doh!)

Cheers now, Mike

LikeLike

Hi Mike. That’s an interesting theory. Also, the algae and lichen (are they the same things) was evident on some of the larger stones on Elsey Crag, especially the Fringpan Stone.

Cheers, Alen

LikeLike

Hi Alen. I like that bunch of strange names. They can surely make your imagination run wild. When you were looking for the Kettle Stone you could have ended up with Malice End for at beginning ???? ????

I tried just for the fun of it to check ‘the strange names’ at the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde but there were no result.

Instead I found an interesting site on Facebook. A DNA Project concerning: ‘Could you be a descendant of a Norse or Danish Viking’ It seems to be several interesting stories on the ‘wall’

I can see you had a pleasant walk despite the missing stone. Lovely landscape and a nice refugee. It’s great to have the opportunity to seek shelter if the weather turns bad.

All the best,

Hanna

LikeLike

Hej Hanna. Thanks for checking the names. It would have been interesting if anything came up. A Viking ship burial would be a great discovery over here. I don’t think we have any ??? although Angle-Saxon ship burials have been discovered.

The DNA project sounds fascinating. I would like to participate in that. I shall take a look.

Yes, the bothy had everything a walker needs, right down to a flushing toilet, which is bordering on the luxurious for these sorts of places. Logs already chopped for the fire and three bowls of steaming porridge already on the table (just kidding).

Cheers, Alen

LikeLike

The address to the DNA Project is: https://www.facebook.com/AffleckDNA

Hanna

LikeLike

I shall look at this now instead of job hunting.

LikeLike

Looks like you found me another local walk Alen. I’ve been meaning to get to Arkengarthdale for a while now, If i get out there and find that Kettle Stone, I’ll let you know……… But don’t hold your breath. ????

LikeLike

Hiya Tracey. If you find the Kettle Stone you must let me know. Have a good walk.

Cheers, Alen

LikeLike

Excellent stuff again, Alen. The local names are a draw in themselves. Crackpot beckons. We trudged through Booze a couple of years ago……just….well, just because.

That day I saved my family, narrowly avoided a fall onto the rocks in Slei Gill, and broke the record for dog-poo bag hurling. I rewarded myself with a curry pie.

This is a very good thing you’re doing, Alen. Thank you.

LikeLike

Hi Steve. Thanks for that. I’ve never walked through Booze. Seen it there on the map dozens of times but have always driven past it. Must get there one of these days. Curry pie? Blimey.

Cheers, Alen

LikeLike

I have tried a couple of time to locate The Kettle Stone and must say I haven’t a clue! It is marked on a map circa 1860 as is a quarry at that position, the path which ends there could well be to do with the quarry. My, rather tenuous theory is that it is either the flat stone (possibly for standing a pot or cauldron for some reason) next to the gate or one of the indented boulders. The approach from Scargill is worth the effort.

Paul Gregory

LikeLike

Hi Paul. The theory about the path ending as it does sounds good. As for the Kettle Stone, I’m wondering now whether the word has the same origins as the geoligical term kettle-hole, as in a depression or hollow. Alternatively, the Viking name Ketil has been incorporated into various placenames and misspelt kettle, as in Kettlewell (Ketil’s well). However, if you ever come across any further information, or stumble across the stone on a future visit, I’d appreciate an update.

Cheers, Alen

LikeLike

By the way, I meant to say what an interesting site you have created: a good read.

Paul Gregory

LikeLike

Thank you very much for that. Greatly appreciated.

LikeLike