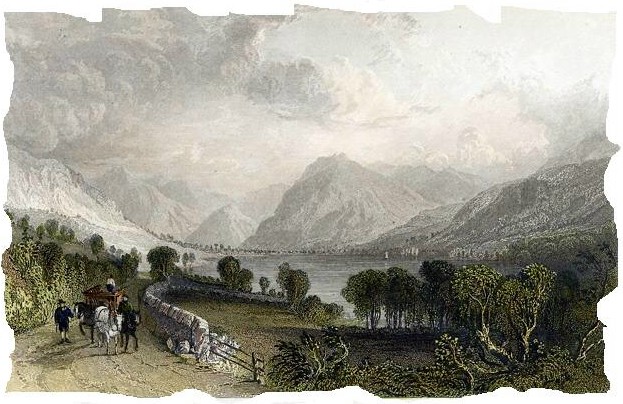

Coledale Hause is the rib of ground in the centre of the picture where two figures are standing (you'll see them if you look carefully or click on the picture to enlarge it). On September 26, 1863, geologist John Bolton crossed the Hause from Gasgale Gill, the valley on the right, to Coledale, the valley on the left, in the search for his Rock Hotel. Nowadays we’d call it a bivvy. Rock Hotel sounds much more sophisticated.

ON September 25, 1863, John Bolton walked the couple of miles from his house in the Furness village of Swarthmoor to catch the early train north from Lindal station. He’d had no breakfast, so on arriving in Whitehaven at 9.30am, he purchased a couple of loaves, stuffed them in his “wallet” – a large bag containing a lump of ham, tin of coffee, and various other comforts – and set out on foot for the western fells, hoping to chance upon a wayside cottage and a friendly wife who would attend to his culinary needs. At Lamplugh Cross he met an old woman called Mary Hastings, who worked a toll-gate.

Bolton was no ordinary man. He’d developed a keen interest in geology in his native Urswick – another Furness village – at the age of five when sifting through rocks thrown up by work men from the sinking of a well behind the village school. He’d spent a couple of decades working as a weaver in Barnsley where he had a run-in with local Chartists who tried – and failed – to appropriate his collection of rifles, before returning to Lancashire North of the Sands and settling in Swarthmoor. Bolton was an eminent geologist, a man who lived for fossils and rocks, and who was as comfortable bedding down among them beneath a starry sky as he was sleeping in his bed. On that fine September morning in 1863, having walked on an empty stomach from Whitehaven to Lamplugh Cross, Bolton was in his 73rd year. He was, after all, no ordinary man.

men from the sinking of a well behind the village school. He’d spent a couple of decades working as a weaver in Barnsley where he had a run-in with local Chartists who tried – and failed – to appropriate his collection of rifles, before returning to Lancashire North of the Sands and settling in Swarthmoor. Bolton was an eminent geologist, a man who lived for fossils and rocks, and who was as comfortable bedding down among them beneath a starry sky as he was sleeping in his bed. On that fine September morning in 1863, having walked on an empty stomach from Whitehaven to Lamplugh Cross, Bolton was in his 73rd year. He was, after all, no ordinary man.

So, to cut an entertaining and highly-colourful story short, Mary Hastings invites Bolton into her rude cottage – the floor of which is fashioned from rocks and is so uneven a table won’t stand without shoggling – and boils a kettle to make his coffee. There then follows a delightful conversation between the elderly geologist and the elderly toll-gate woman, which is reproduced verbatim in Bolton’s book: Geological Fragments of Furness and Cartmel 1869, in the chapter entitled “Geologising Under Difficulties”.

So, to cut an entertaining and highly-colourful story short, Mary Hastings invites Bolton into her rude cottage – the floor of which is fashioned from rocks and is so uneven a table won’t stand without shoggling – and boils a kettle to make his coffee. There then follows a delightful conversation between the elderly geologist and the elderly toll-gate woman, which is reproduced verbatim in Bolton’s book: Geological Fragments of Furness and Cartmel 1869, in the chapter entitled “Geologising Under Difficulties”.

Mary is curious to learn what an elderly gentleman from the Furness peninsula is doing in the western Lakes, with his bulging wallet, can of coffee and Whitehaven loaves. Is he prospecting for iron ore, like so many people “frae Forness”? Bolton tells her he is off into the mountains in search of interesting rocks and intends to spend a couple of nights there. Mary remains sceptical:

“I would like to knaw hoo ye are provided wi meat; hoo ye will cook it; an’ hoo ye will contrive ta sleep?”

Being willing to satisfy her in this, we took out our wallet, and emptied it on a long black oak table, that stood before the window, and said “you see I have plenty of bread, and I have two or three pounds of boiled ham in this newspaper, some ground coffee in this small canister, and some butter in this canister, and plenty of sugar in this paper, and here is a tin can that will hold a pint; this is a very important utensil, for it is my kettle, my coffee-pot, and also my coffee-cup. As for sleeping, you see I have a top coat on my back, and I have an old wallet inside this new one; this will be my bed, besides I have a box of matches in my waistcoat pocket, to keep them dry, and I think I am not badly provided.”

Mary is mightily amused by the wallet and its contents. It has not escaped her observation that the wallet, which is to be Bolton’s bed, is only half the length of his body. And there’s another problem the geologist can expect to encounter: there are very few places in the Cumberland fells where the ground is dry enough for an ageing man spend the night.

“Thar is nea a yard o’ dry ground on a’ oor mountains. Will ya lay doon on the damp ground, or, maybe, in the wet an’ mire?”

Bolton is not easily deflected. This is a man, after all, who successfully repelled an angry mob of Chartists attempting to deprive him of his personal arsenal. He might be in his 73rd year, but he is made of stern stuff. In fact, it will become clear as this article progresses that he is made of extremely stern stuff indeed. Bolton is as hard as the rocks he worships. He is as contented in the dripping shingles, shales and screes of Lakeland as the graptolites and trilobites entombed within. He responds:

“I will tell you how I have done in a case like that, and it will be a lesson for you when you sleep on the mountains.”

“Nay, me man, but ye’re joking, noo; but I hope I’ll nivver lay on’t ground until they lay me in Lamplugh Churchyard, whar o’ me kith and kin are laid. Hooivver, ya may let me know.”

It should be borne in mind that this conversation – these extracts from which are but an infinitesimal part of the original published version – was recorded some time after the event. Bolton did not possess a laptop. He did not even carry a pen and paper. These words were jotted down from memory, in all probability several days, perhaps even weeks, after he sat in Mary Hastings’ house supping coffee. We can, therefore, allow him some leeway – a little poetic licence. He is a man writing a book. And he has reached a crucial juncture where he needs to make a point. Bolton is building his story and has reached a high plateau but needs to go higher. He is, to employ a geological term, about to have an orogeny.

“Well, you see, Mary, five of us agreed to sleep on the top of Scawfell, and there were the ruins of a place made by the Ordnance surveyors. It was about as high as your table, but it was very damp, so we laid flat and dry stones side by side, where we intended to sleep, and made it something like your rough floor. Whenever I attempt to sleep on the mountains I will do the same; but, indeed, Mary, there is nothing so very terrible in it after all; and, besides when we patronise the ‘Rock Hotel,’ it is some comfort to think that there is no landlady to come to you in the morning, with a little bit of paper in her hand, with so much for supper, so much for breakfast, so much for bed, and so much for attendance; you see nothing of this. All you have to do is return thanks to the Almighty for watching over and preserving you through the night, and go your way with thankfulness and a cheerful heart.”

That final sentence must have been written with genuine thanks to the Almighty – or possibly irony. For Bolton’s night in his “Rock Hotel” would be immediately succeeded by one of the most uncomfortable days of his life. Indeed, it would prove to be almost fatal. The geologist, though, had set the scene for his night in the fells at the start of the chapter:

As we have had some little experience in sleeping on the mountains, viz., Dow Crags, Walney Scar, and on the top of Scawfell, we contemplated doing the same in this instance, as it is very unpleasant to travel to an inn at nightfall, and to return to the same place in the morning. On all our Green Slate mountains there are many sheltered nooks among the rocks, so that any man in health may, during seven months of the year, take a few nights’ lodgings in some of them, with comparative comfort, especially as he may have his choice of bedchambers, with sometimes a nice soft bunch of heather for a pillow. The Skiddaw Slate mountains do not afford the same shelter as the Green Slate and Porphyry, the principal part being soft, and wasting rapidly by atmospheric influence, so as to break down all precipitous rocks and leave the surface comparatively smooth and even.

Bolton is motivated by an energy more noble and erudite than the desire to spend a night in the mountains. He has a mission: to chip away at the rocks of Causey Pike, above the

Newlands Valley, with his geological hammers in search of the fossilised remains of tiny creatures that perished millions of years before the mountains existed. His goal is knowledge and understanding, his ambition to build on the foundations laid by great predecessors and contemporaries – most notably his friend, Cambridge professor Adam Sedgewick – and shine a beacon for those who follow. But in common with another contemporary, author Robert Louis Stevenson, he shares an appreciation for the journey. “To travel in hope is a better thing,” wrote Stevenson, “than to arrive.” Bolton is certainly travelling in hope – and relishing every minute of his journey. Fossils might be his objective, but a ride on a train in the days when railways are in their infancy, coffee with Mary Hastings and the prospect of a night beneath the stars are all part of his bigger picture. This might be a geological excursion, but it’s an adventure as well.

Bidding Mary adieu, Bolton wanders towards the mountains, pausing only to examine rocks in roadside quarries before enquiring for lodgings at a Loweswater inn called the Hare and Hounds (now the Kirkstile Inn).

After laying by our wallet, we repaired to the kitchen, where there were three sheep farmers, conversing on sheep and shepherding. This was just the company we wanted, as we thought to make some inquiries respecting the great and comparatively unknown block of mountains between Crummock Water and Keswick, which it was our intention to penetrate and explore in the morning; but we were surprised to hear that none of these farmers had ever been over them in their lives, although they had been on all the other mountains within many miles. Even the landlord, who was a great hunter, knew nothing about them . . . We were strongly advised not to go that way, for we would find it rougher than we thought; but these shepherd farmers did not know that it was the roughness we wanted, and as for the direction we ought to travel to reach Causey Pike or the village of Braithwaite, we were as well acquainted with it as any shepherd in Cumberland.

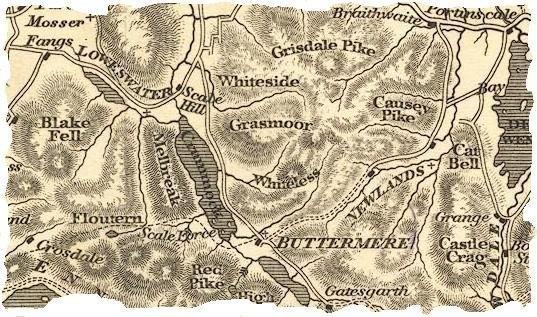

The mountains to which Bolton refers form the group situated to the south and west of Keswick, and north of Buttermere and Loweswater, and include Grassmoor, Whiteside, Hopegill Head, Crag Hill, Grisedale Pike and Causey Pike. They are formed of the oldest rocks in the Lake District, the Skiddaw slates, which were laid down in deep water during the Ordovician period about 500 million years ago. The Skiddaw slates are softer than the Borrowdale volcanic series of rocks that form the central hub of the Lakes and the craggy southern fells, hence their more rounded appearance. That’s not to say they are not wild and dangerous. They are both. These north-western fells may not possess the spectacular crags of Wasdale or Langdale, but there are still plenty of places where a bloke can plunge several hundred feet to his death.

The following morning, Bolton shoulders his wallet and, against the advice of the shepherds and landlord, wanders off into the mountains. His route can be traced from his notes. Pausing occasionally to root for fossils among the rocks, where he is cheered by finding “a rather good specimen of the new crustacean caryocaris Wrightii”, Bolton makes slow progress along the rocky Gasgale Gill, between the fells of Whiteside and Grassmoor, before clambering to the crown of Coledale Hause – a strip of rock that forms a bulwark between the head of the gill and the head of neighbouring Coledale, the valley that runs down to Braithwaite. The geologist has wandered only a few miles from the inn, but his geologising – his fossil hunting and theorising on anticlinal valleys – has slowed his progress. It’s time to search for lodgings – his Rock Hotel. Bolton descends from Coledale Hause and skirts beneath the screes of Eel Crag and Sail towards an old cobalt mine on the western end of Causey Pike.

The first thing was to look out for a lodging, and we began to think we should not have passed the old mines, however, we would not go back again, but there being no friendly nooks among the rocks, we went forward to an old sheepfold we had seen in a former ramble. This was a square inclosure, the walls being about five feet high, and ground wet and miry all over. There was a sort of gateway on the east side, and an old gate or hack was lying on the ground, formed out of four bars about a yard long, roughly nailed together. We carried this to the west or sheltered part of the inclosure, to be used as a bedstead, and not a bad one either, only it was about three feet too short.

Like a true mountain wanderer, Bolton prepares for his night beneath the stars. He empties his wallet and places his canisters of coffee and butter in holes in the sheepfold wall. He stashes his ham in another hole out of the wind. He unravels his wallet and stretches it out on the old gate he has found. He stuffs the Whitehaven loaves inside the wallet to use as a pillow. Then he gathers heather and bracken to kindle a fire for his coffee. But the wind “whiffles” smoke in his eyes, so he allows this to burn down before warming a can of bog-water – there being no stream in the vicinity – in the ashes.

We were now, really and truly, in the mountains, far from the dwellings of man, and from the voice of every living thing; there was not even the bleating of a sheep to disturb our meditations, but there was the sighing of the wind amongst the heath and rocks above, and the rushing of the water below, which in Holy Writ has been called the Voice of God.

Bolton spends an uncomfortable night with his legs dangling over the end of the four-bar gate. At one point he gets up, extends his bed with stones from the wall, and returns to his wallet, wrapped in his top coat, while clouds scud across the moon. The night beneath the stars has turned into a religious experience – and his Saviour smiles caringly upon him, even though the gate is uncomfortable and his legs are wet from dangling in the mire. But in the morning, after breakfast and another can of coffee, he sits in his Rock Hotel watching the clouds gather on the mountains and the wind whip into a frenzy. God may have guarded him during the darker hours, but now the daylight has broken the Almighty has abandoned the mortal to the elements – despite the fact Bolton has vowed not to seek for fossils today because it’s Sunday.

It was not long, however, before it thickened on all sides and began to rain in earnest, the wind increasing to a storm; but from the strength of the wind we did not think the rain would continue long, and we should have been thoroughly wet before we could have reached the old cobalt mine, otherwise we would have adopted a scheme to have kept all our clothes dry except our great coat. Here we sat on the gate, crouched up, with the umbrella over our head, but it would not cover us entirely, so that there was a stream of water running down us either on one side or the other, and we found also that water was running down the inside of the wall and down our back. At length we became wet all over, and there was no sign of the rain ceasing, as hour after hour it poured down without any intermission.

Bolton toys with the notion of making a dash for the cobalt mine and sheltering in the workings while the storm rages over the mountains. He discounts this as unpractical. He would have to toil all the next day in wet clothes. He then considers abandoning the mountains altogether and making for the nearest human habitation, which is the village of Braithwaite. Then, without warning, a stream bursts through the sheepfold. This focuses his mind.

We had hoped the rain would cease about twelve or one o’clock, but the storm increased, the rain becoming heavier, and about that time a stream of water burst through the north wall of the inclosure, (that being the higher side), and ran under the bed. The gate-bedstead, however, kept us out of it; though it did not matter, for we could not be much wetter, still we did not like to be intruded upon by this new river, so with our geological hammer we made a trench and turned it another way.

Two o’clock comes, with still no sign of the storm abating. Then three, four and five o’clock. If anything, the storm has become even worse. And soon darkness will fall. So Bolton stows his goods in holes in the wall, thrusts his umbrella under the gate, takes one of his wallets on his shoulder, and strides out into the wind with the intention of making for Braithwaite.

We now found the value of the wall as a shelter from the wind, for it was with the greatest difficulty we could stand, although our road was in the direction the wind was blowing, and we could not possibly have gone against it.

Bolton reaches the old track from the cobalt mines to Newlands Valley and heads north along it, bent almost double and buffeted by the gale. Progress is slow. But his troubles are only just beginning. He is not prepared for the ferocity of the wind he is about to encounter.

Although it was difficult to stand near the inclosure, we found we had not got into the real current of the storm down this gorge [Stonycroft Gill], which was confined by a mountain on each side, which intensified its effect to such a large degree that we believe no man could stand before it. Soon after we came to the road we heard a sound behind us, not like that of the wind, but more like thunder at a great distance. We had not gone twenty yards when a great gust of wind swept us down instantly. It was at the turn of the road so that we fell against the hill side, lying flat on our face, we held on by the heather until it had gone by – had we been in a straight part of the road at the time, we should have fallen on the other side and come to an untimely end. We laid a few seconds until the gust had swept by, then rising carefully, and with difficulty, we attempted to return to the inclosure, but we found that to be impossible, therefore we must go forward at all hazards. We accordingly turned in that direction and had not advanced more than thirty or forty yards before we heard the hurricane coming behind us, so we instantly fell flat on our face, and held by anything we could get hold of until it had passed over. We had now gained some little experience, and as the sounds of these tremendous gusts gave notice of their approach, we always laid down flat on the ground, sometimes holding by the heather, sometimes by scratching with our hands into the shingle or any roughness in the path.

We’ll leave John Bolton there for now, clinging to roots as hurricane-force winds rip through the high valleys, rain continues to fall in torrents and darkness envelops the mountains. But don’t worry, he’s a man in his 73rd year so he’s old enough to look after himself.

SO. A hundred-and-forty-eight years later, I’m sitting in a car at the Braithwaite end of the Force Crag track while rain hammers on the windscreen. It’s not a day for tramping the fells, and if my destination had been anything other than John Bolton’s Rock Hotel I would have turned the car around and retreated along the A66. But, in reality, it’s the perfect day to search for the place he slept uneasily on his four-bar gate. I can’t, in all honesty, call myself a mountain man if I am to be deterred by rain and gales when a 73-year-old geologist braved a great deal worse in a top coat and hob-nail boots.

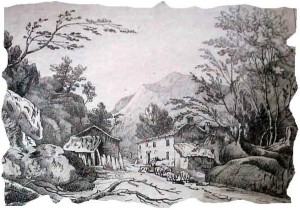

The road from the cobalt mines along which John Bolton crawled and stumbled in the teeth of a hurricane-force gale. Causey Pike is the fell to the right.

I have no wallet stuffed with Whitehaven loaves and ham wrapped in newspaper. But I have a Tupperware box containing a famous brand of oatcakes, half a Polish sausage, some dates with fluff stuck to them that I found in a rucksack pocket, and an assortment of energy bars. Neither have I in my possession a canister of ground coffee and a box of matches, but I’ve a £2.99 flask from the Wilco store in Darlington that is full of green tea. This might sound like cheating, but it’s not my intention to spend a night on the fells. And I’m not 73 either.

The purpose of this exercise is to locate Bolton’s Rock Hotel. I have availed myself of a large-scale Ordnance Survey map that shows three sheepfolds in the area where he must have camped. I’ve also compiled a list of criteria for eliminating non-runners with information gleaned from Bolton’s account. The Rock Hotel must:

- Be within view of the cobalt mine

- Be squarish

- Have walls 5ft high (I shall allow for wear and tear)

- Have a gate in its east side

- Be in view of Causey Pike

- Have its north wall as the higher, uphill, side

- Stand about 100 yards from the cobalt mine track

Braithwaite is an empty, cold and desolate place on a cold and desolate day. Nothing moves except the telephone wires as I clump through the streets towards the High Coledale track. This is Bolton’s line of descent – roughly – from his hurricane hell. It takes him several hours to stagger and crawl along the short length of mine track that skirts the upper section of Stonycroft Gill, before finding comparative shelter in Barrow Gill beneath the northern slopes of Stile End. But his troubles are far from over. His intention is to make for High Coledale, a farm halfway down the fell, but in the darkness he finds himself on the wrong side of Barrow Gill Beck, which is in a state of flood in its rocky defile.

This stream is a branch of Braithwaite Beck, so we followed it down towards the village, thinking to find a bridge, but there was neither a bridge nor a place where it could be crossed with safety; at length, when we came near the village, we were stopped entirely in that direction and had to go partly round the south side of the village, through some rough fields, and enter it by the public road at last. It had now been dark for upwards of two hours, and those trifling mishaps were rather annoying, but there was nothing dangerous after leaving the storm-valley, where our whole thoughts were concerned on our own personal safety.

We can now breathe a sigh of relief. Bolton is ensconced in the Royal Oak, where the landlord presents him with a set of dry clothes and makes him promise not to return to his geologising until the storm has passed. Fat chance of that. Meanwhile, back in the present, I follow the track up the gill into the wind and slanting rain to High Coledale and discover a rather impressive ruined farmhouse beneath tall trees.

Barrow Gill, with the summit of Causey Pike in the background. Either this path did not exist in the 1860s or Bolton missed it in the dark, because he descended the gill on the opposite flank before getting into difficulties.

The farm looks as though it hasn’t been occupied since Bolton’s time. But a quick clatter through Google reveals that a planning application for improvements to the house and adjoining barn was approved as recently as 1983. The agent was Fred Reeves, from Coniston, a name that is sure to ring bells in fell-running circles.

The farm looks as though it hasn’t been occupied since Bolton’s time. But a quick clatter through Google reveals that a planning application for improvements to the house and adjoining barn was approved as recently as 1983. The agent was Fred Reeves, from Coniston, a name that is sure to ring bells in fell-running circles.

I continue on my way as the rain clatters down, and just beyond the head of the gill find my first sheepfold: a sturdy affair complete with boggy ground both inside and out, and copious clumps of that tall, spiky plant that might be marram grass but probably isn’t. My spirits rise as, one after another, the criteria boxes are ticked off – all except one. This sheepfold is not within sight of the cobalt mine. It’s a good mile to the north-east. Bolton would have crawled and stumbled past this sheepfold on his terrifying descent. He might even have clung to the very clump of spiky grass I’m sitting on to take my brew while the deadly gusts roared across the fellside and darkness rolled in like an evil tide. But one thing’s for certain: this sheepfold, despite its likeness in almost every aspect, is not the Rock Hotel.

The mine track from Stonycroft winds up the fell beneath the summit of Outerside and I follow it into the storm, which is now becoming uncomfortable. Near the head of Stonycroft Gill I stumble upon the second sheepfold. It can be discounted immediately because it’s right next to the track and only a few yards from the beck. The Rock Hotel had no beck – Bolton made his coffee with bog water. But a pattern is beginning to emerge. The second fold is exactly the same shape and size as the first, with the gateway being in the east side – just like Bolton’s shelter.

My large-scale Ordnance Survey map, which at this point I must confess is not the genuine article but was downloaded from the internet last night and printed on inferior paper, begins to disintegrate like a pocketful of tissues that have been through the wash. I’m not too concerned because the ink started to run an hour or so ago, producing an effect that, under different circumstances, might have been considered pleasing to a student of watercolour landscapes.

On the crest of the ridge where the wind and rain are strongest – the south-west slope of Outerside – I discover a scattering of stones that has the appearance of being the remains of a structure of some kind, about a hundred yards to the north of the track. If this is a ruined sheepfold then it isn’t on the map. I clump about among the stones, somewhat disconcertedly because it’s thrown me somewhat. The unnerving thing is – this mysterious pile ticks every single box. The location, the views, the surroundings, everything feels right. But, and this is the big but – is it an old sheepfold? Or is it just a pile of stones?

A pile of stones. But is it a special pile of stones? Is this the ruin of a sheepfold where John Bolton spent an uncomfortable night – and an even more uncomfortable day? That’s Causey Pike in the background, by the way.

A few hundred yards further on, and a hundred yards beneath the track in the bowl of Long Comb, I find the third sheepfold. This offers great hope because it sits directly on a faint path from Coledale Hause, the route Bolton would have taken. Again, its four walls adhere to the familiar pattern, with the gate being in the east side. One minor niggle is I can’t see the summit of Causey Pike from where I crouch in the shelter of a wall. But, I argue as the rain slants in, it sits right beneath the cobalt mines, and the cobalt mines are on the western end of the Causey Pike ridge. So, technically, I am looking directly at Causey Pike.

Another minor niggle emerges. The north wall is on the lower side of the slope, not the higher. Huh. But I’m relying on the guesswork and memory of a septuagenarian here, a bloke who was gathering material for a book and who liked to tell – perhaps embroider – a good tale for the sake of entertaining his readers. There is no doubt he jotted down his account many days after the event, when his memories – like the leaves in that long-ago September – were fading fast. He’d been through an ordeal. Perceptions would have altered; details become muddled, recalled, reassembled, and presented as fact. But is this sheepfold in the bowl of Long Comb, this lowly structure beneath Causey Pike’s western screes, John Bolton’s Rock Hotel? Hmmm . . . Where are the Whitehaven loaves?

Another minor niggle emerges. The north wall is on the lower side of the slope, not the higher. Huh. But I’m relying on the guesswork and memory of a septuagenarian here, a bloke who was gathering material for a book and who liked to tell – perhaps embroider – a good tale for the sake of entertaining his readers. There is no doubt he jotted down his account many days after the event, when his memories – like the leaves in that long-ago September – were fading fast. He’d been through an ordeal. Perceptions would have altered; details become muddled, recalled, reassembled, and presented as fact. But is this sheepfold in the bowl of Long Comb, this lowly structure beneath Causey Pike’s western screes, John Bolton’s Rock Hotel? Hmmm . . . Where are the Whitehaven loaves?

In the morning, as soon as breakfast was over, we set out for Causey Pike, the weather being rather wild and showery. We made direct for the sheepfold as our two hammers and chisel were there. We found everything as we had left them the day before, the canister in the wall, being watertight, was no worse; the ham only a little wet, and the newspaper was washed to pieces; the loaves had gone to paste again, but that was a trifle as we had promised to sleep at the Royal Oak again; but in future we will make no promises of that sort, but leave ourselves at liberty to patronise the “Rock Hotel” if it suits us.

Bolton spreads his wet clothes on the ground, pins them down with rocks to dry in the wind “so that it looked rather like washing day”, and immediately sets to work with his hammers and chisel demolishing Causey Pike. Because this, really, is all that interests him: caryocaris Wrightii, diplograpsus pristis, graptolies Sagittarius, G. Tennuis.

And me, I leave him to it and wander in the other direction, with the wind and rain at my back, down to the silent sheds at the abandoned Force Crag Mine and the stony track along Coledale that leads to Braithwaite. Somewhere high above me to the east is John Bolton’s Rock Hotel. It’s not the sheepfold in Long Comb, I’ve decided. It’s not the fold by Stonycroft Beck or the one with the spiky grass. But the next time I’m up there – hopefully on a better day – I’m going to poke about in that mysterious pile of stones that ticked all the boxes to see if I can find the nails of a four-bar gate. Or some strange lichen-like growth that was spawned by the mould of two Whitehaven loaves.

What a wonderfull story, and one I shall remember when I think that I’m roughing it on windy wild camp wrapped in hundreds of quids worth of gear.

It puts things into perspective somewhat, Karl. I think people were made of different stuff in those days.