The irreplaceable Eric Holland leads a gang of Cumbria Amenity Trust members as they haul oil drums to Wythburn Mine, December 1981

IT???S December 1981. Two young men dig deep into the snow at an altitude of 2,000ft on England???s third-highest mountain. Six feet down they strike wet scree. The air is so cold that the scree freezes as they dig ??? so they tunnel through it. All afternoon they toil with pick-axe and shovel. Then as the sun goes down there is a rumble and a sudden rush of stones. A black gulf opens up at their feet. ???Bloody hell,??? says one. ???We???ve knocked a hole in Helvellyn.???

There???s a back-story here. It???s about obsessions. Obsessions are dangerous. They gnaw at your insides and sap your mental energy. They stand in the way of things they shouldn???t stand in the way of.

This obsession began in 1981 when I stumbled across an obscure mineral venture high above Thirlmere: Wythburn Mine. Struggling up Mine Gill one hot July day I discovered all sorts of stuff: ruined buildings; a derelict inclined tramway; spoil heaps; smashed equipment; all hidden in a deep fold of Helvellyn where no one ??? and I mean no one ??? ever wanders.

There are hundreds of old mines in the Lake District, but this one was different. Very little was known about its history; very few people were aware it existed; no living person had explored its depths. Only a smattering of records survived the century that had elapsed since the mine closed. Only a few sparse paragraphs appeared in WT Shaw???s bible: Mining in the Lake Counties. Little was known about the extent of its workings because all the tunnels had been sealed when Manchester Corporation acquired the valley for its Thirlmere reservoir scheme in 1880. But there were gravestones at Wythburn??Church bearing names that could be linked to the miners ??? and one in particular: Arnison. Wythburn Mine was, in effect, an obsession waiting to attach itself to the back of an impressionable passer-by.

So a few months after that pleasant summer excursion, on one of the shortest and coldest days of winter, there???s Chris D Jones and me digging through snow, boulders and freezing scree in an attempt to break into Wythburn??Mine???s No. 1 Level ??? the middle of three tunnels that penetrate the mineral veins over a vertical height of 300ft. I???d been beaten back on a solo attempt a few weeks earlier. But this time, in a sudden rush of stones, this great black hole opens up and a gust of warm, earthy air belches out. I can???t see a thing because the air steams up my glasses. All I know is that we???ve broken into something big.

DECEMBER 23, 1981: The first ten feet, where the tunnel runs through the scree, is timbered and in an unstable condition. After that it runs through good solid ground, following the line of the Old Vein. Several back-filled passages branch off here and there, and in one place the level opens out into a quite sizeable stope??[a void where the vein has been mined away]. Two-hundred feet from the entrance is an upturned wooden wheelbarrow lying in the passage and an improvised bench for miners to sit and take their bait. Three-hundred???and-fifty feet in I hear cascading water ??? and there, above my head, is an impressive void, down which a plume of water is crashing. The water surges through our tunnel in a curtain of spray. Twenty feet further is a black chasm in the floor down which the water plummets. I regard it, spectacleless, with mixed feelings of horror, jubilation and dismay. This, it appears, is the route down to No. 2 Level ??? the main section of the mine.

It???s Christmas Eve, and McFadzean prepares for the main festival of the Christian calendar by knocking the ends out of two oil drums and swilling them out with warm water and his girlfriend???s mop. Christmas in Cumbria during the 1980s was always a frugal affair. But we knew how to have a good time

The following day, Christmas Eve, I purchase two 40-gallon oil drums from a scrap dealer in Dalton-in-Furness and bash the ends out with a hammer and chisel. I know that once the thaw begins, the scree will rush in and Wythburn Mine will be sealed for another hundred years. The drums will secure the entrance. Three days later, I chuck them in the back of my Escort van and head off to Thirlmere to meet a load of Cumbria Amenity Trust Mines Historical Society members. Things are coming together.

DECEMBER 27, 1981: We can???t get into Wythburn??car park because it???s snowed up, so we gather outside on the road. Equipped with ice-axes, ropes, crampons, and hauling the drums, we make the 2,000ft??ascent to No. 1 Level in Alpine conditions. At times the wind and spindrift are so severe we are forced to lie in the snow and hang on to the drums while the elements blast. Nine members make the ascent. They will not forget it quickly.

Chris Jones and Max Dobie hauling oil drums 2,000ft up Helvellyn in the snow. It's something to do on a quiet day in winter

Obsessives are not necessarily isolated people. When a few of them get together they have a really good time. Once at the level entrance, these enthusiastic blokes thrust the drums in the hole, pack them with scree and rocks, and slither through into the newly-opened??reaches of No. 1 Level. We spend a pleasant couple of hours poking into corners and decide that the waterfall must originate in Arnison???s Low Level, 150ft??above, thunder down a worked-out stope??to No. 1 Level, where we are now, then plummet down another stope??to the mine???s main tunnel, No. 2 Level, 150ft??beneath our feet. That???s some waterfall. What a discovery. The downside is, though, that someday soon we shall have to abseil down it.

Two months later, after the snow has melted, I return with Eric Holland, Mark Wickenden??and Chris Jones to abseil??down the waterfall. Mark goes first, followed by me. Wisely, Eric and Chris stay at the top. People who have abseiled??150ft down a curtain of freezing water wearing shipyard overalls will have an idea what an excruciating experience this is.

Two months later, after the snow has melted, I return with Eric Holland, Mark Wickenden??and Chris Jones to abseil??down the waterfall. Mark goes first, followed by me. Wisely, Eric and Chris stay at the top. People who have abseiled??150ft down a curtain of freezing water wearing shipyard overalls will have an idea what an excruciating experience this is.

FEBRUARY 1982: There is a problem. During the cold spell the volume of water flowing down the void had been a comparative trickle. Today there is a veritable Niagara. We regard the situation dubiously before rigging the pitch. Mark descends first, followed by me. The descent is spectacular. Once past a short inclined section it drops into an immense stope, which defies description. I find Mark on a ledge near the bottom sheltering from the spray.

We have a look up a short tunnel, waist-deep in water. And that appears to be it. Nothing else. Disappointed, we shuffle about in the debris feeling cold, wet and quite miserable. Then Mark dislodges??some rocks and a hole appears. We rumble down through this mass of perched boulders and drop, literally, through what has once been a wooden ore??hopper into a grand, spacious level. And, my God, it is endless. No. 2 Level goes on and on, branches here, branches there, old zinc air ducting, piles of barytes, clevis hooks, shovels, wheelbarrows. We spend the best part of an hour poking about.

Then we face the inevitable: the ascent of the waterfall to No. 1 Level on electron ladders, with Eric and Chris on the lifeline.

There???s something about potholing, something romantic, that captures the imagination of the adventurous. I was captured at an early age. I think it was the allure of majestic chambers walled with rare crystals and cavern roofs bedecked with elegant stalactites and curtains of coloured calcite that did it ??? or perhaps a primeval instinct that told me caves are places of warmth and safety, where the glow of firelight flickers in the shadows and thoughtful men paint bison on the walls.

Fifty feet up the wire ladder, with freezing water pounding my helmet and shoulders and ripping the air from my lungs, I make a mental note to revise this misconception. I am blinded by spray. My fingers won???t function because of the cold. I can???t hear a thing above the deafening roar of water. The ladder??is spinning. There are no bison on the walls and no elegant stalactites. All that exists is water, air, noise, extreme cold ??? and the flimsy ladder. I vow never, ever, to abseil down the waterfall again. Curious, then, that I???ve done it at least five times since.

SEPTEMBER 1982: Seven of us meet in the rain at Wythburn??Church. The source of an unpleasant smell in my van is revealed when a dead mouse falls from my left welly while I???m getting changed. This amuses Ronnie Calvin no end. By the time we reach the mine the sky is blue and the sunshine glorious. Alas, the waterfall is in full spate and seems even more unappealing than it did in February. Undaunted, and wisely garbed in neoprene, we abseil??down the stope impervious to the thundering spray.

I return to Wythburn??Mine on dozens of occasions over the years, mostly on solo trips to poke about among the ruins. In August 1983 I dig open No. 4 Level in the forest, and explore and survey it. Nothing of much interest there, just a 600ft??tunnel and some rotting air ducting. But like a dangerous enchantress high in the mountain, the waterfall is always calling.

JUNE 20, 1987: We set off, Bert Wheeler and I, in the Land-Rover at 8.10am, arriving in Wythburn a little after 9am. After a brew we poke around in No. 4 Level then head up to No. 1 Level in the sunshine. We have a bite to eat before crawling through the oil drums at the entrance.

We take a couple of photographs of the stope??in the Blue Rock Vein, a couple more where the barytes and galena show at the end of the level, then rig the pitch for the descent to

No. 2. There is slightly less water than usual cascading down the shaft ??? only a little less, mind you. I put in an extra bolt just where you drop over the final ledge

into the big void for a little extra protection and to help keep us out of the main body of water. When we???re both safely down we take some pictures of the gear left by the miners ??? a wooden wheelbarrow, jumpers (rock drills) and ladder. In Nicholson???s Crosscut I discover a two-legged stool propped in a corner ??? perhaps the very seat where Isaac Nicholson used to sit to have his bait.

Bert has never prusiked before, but he performs well on the rope going back up the waterfall. After I join him in No. 1 Level, we pack up the gear and return to the sunlight. It???s a perfect summer???s evening. To round off, we stop for a pint in the Travellers??? Rest in Grasmere.

The waterfall: where does it come from? Will its source, like the Holy Grail, ever be found? All we know is that it comes hurtling out of the roof of No. 1 Level, from an ugly black void. Up there, higher up the mountain, lies Arnison???s Low Level.

JUNE 28, 1987: I land at Wythburn??Church just before 9am and I???ve got the kettle on when Ian Tyler and Dave Ramshaw??roll up. It???s raining heavily, but we set off for the mine after a brew and reach Arnison???s Low Level just after 11am. There is no obvious site for the level entrance, just a slope of grass and scree above a sizeable spoil heap. A series of trial digs ??? four ugly holes in the fellside ??? reveal absolutely nothing. Then at about 3pm Dave digs up some timber right in the middle of the site. We soon have a hole poked down into the level below.

By the time we have dug the scree back sufficiently to enlarge the hole, it is 5.10pm. Ian pokes his head into the level and reports that there is a total collapse just a few feet further on. I have a quick look. The collapse, which has occurred in the masonry lining, looks undiggable??because of the instability of the passage and the loose scree directly over the entrance. We are very disappointed. John Arnison must be smiling to himself ??? wherever he is. There again, he might be disappointed.

Thwarted. But the waterfall continues to call.

NOVEMBER 22, 1987: Up early and heading north before daylight to meet Ian Tyler at Wythburn Church. I arrive at 8.35am to find Ian already there with a young lad called Warren Allison. By 10.35am we are up at No. 1 Level, having poked around on the No. 2 tip which ??? we are surprised to find ??? has been practically washed away since our last visit.

We soon have the pitch rigged. I go down first, suffering considerable discomfort from the pounding water as I rig an extra belay 40ft??down. There is a large volume of water crashing down the stope??today, could even be the wettest I have ever seen it. Down on No. 2 Level things certainly are wetter, the passage beneath the stope being chest-deep in places.

Ian has very sharp eyes and spots many things I have missed on previous visits. Most interesting is a ball of mud on the tunnel wall with the stub of a candle in it. Not an uncommon sight, one would think. But this still has the miner???s fingerprints embossed in the mud. Those fingerprints have survived more than a hundred years. Like the clog prints in the mud of the floor, they are a human link to the men who toiled here.

We get back to the surface at 3pm to find a smattering of snow on the crown of Helvellyn. It???s been a bloody cold day, but enjoyable in a masochistic sort of way.

During the Vickers shipyard strike of 1988, which lasts 13 weeks, the waterfall calls yet again. This time I am accompanied by Neil Pacey and we???ve spent the previous night in the Barrow Mountaineering Club Hut at Coniston after a day poking about in the copper mines. This makes a change from attending mass meetings and marching behind the shipyard band.

JULY??19, 1988: After a breakfast of bacon, eggs, sausage, beans, tomatoes, toast and tea we set off for Thirlmere with the intention of making a photographic tour of Wythburn??Mine. I don???t remember much about last night except having a couple of pints in the Crown and singing Pogues songs with some chaps in the hut. I think my rendition of The Old Main Drag went down quite well. It???s mid-afternoon when we arrive at the No. 1 Level oil drums.

After photographing all the interesting bits of No. 1 Level, Neil rigs the pitch and we abseil down to No. 2 Level in a cold and voluminous surge of water. We then do a complete tour of the workings, taking multi-flash pictures of all the interesting features.

The long prusik up is icy cold. I have given Neil my gloves because he???s climbing last and de-rigging the pitch. My hands are completely numb and my knuckles are bleeding ??? but I can???t feel them. To make matters worse, the crashing water keeps dousing my carbide lamp. I have to keep stopping to rekindle the flame. In the end I give up and spend much of the ascent in complete darkness.

Our efforts are rewarded when we emerge from the oil drums into the glorious heat of the late afternoon. We reach the car park at 7pm and cook a supper of sardines, beans, lemon tea and a Marathon before heading for home.

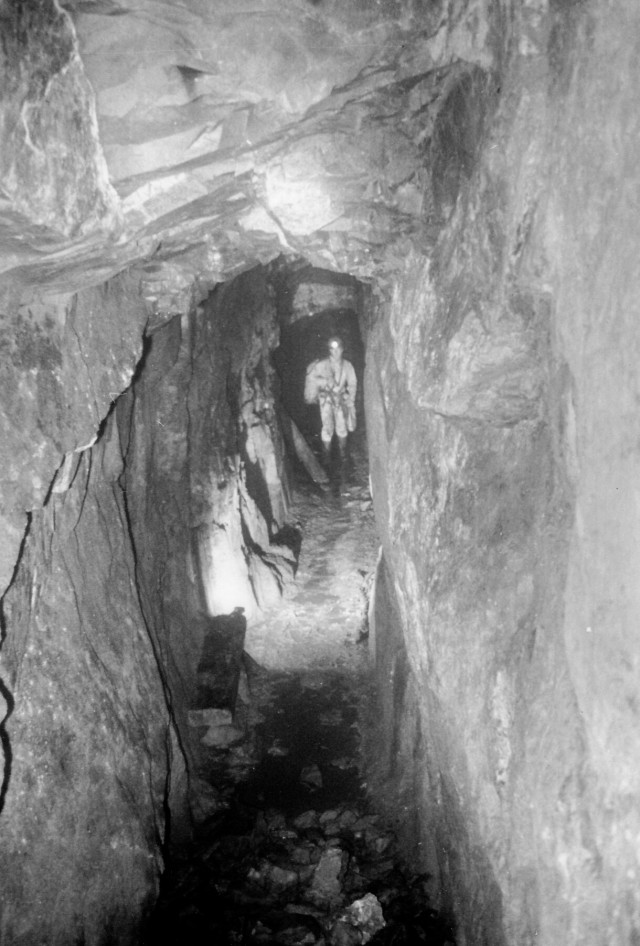

Neil Pacey in Wythburn Mine's No.1 Level. The bench on the left was for miners to sit on and take their bait

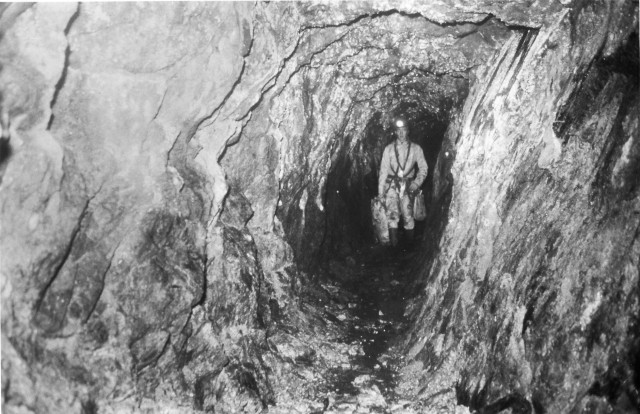

Neil Pacey prepares to ascend the waterfall at the foot of the big stope on No. 2 Level, Wythburn Mine, July 1988

Exploratory digs at Wythburn??Mine continue. A gang of us have a crack at opening No. 3 Level, on the fellside??below the smithy, but this ends in failure. Then Ian Tyler and his friends finally break into Arnison???s Low Level and discover the source of the waterfall percolating??through cracks from the surface. On my final ??? or most recent ??? trip underground there, the date of which escapes me, I finally get to see this stream of subterranean water plunging over a ledge to begin its 300ft??descent into the blackness. And I think: men used to work in that; miners carved that void with hammers, jumpers, black powder and fuses for galena, the ore of lead; they climbed 2,000ft??every day to toil in the wet and the dark, then trudged 2,000ft down again ??? and all for a pittance and an early death.

And here I am, three decades after my first visit, sitting on a collapsible stool as the snow lies deep in Wythburn Church car park, a pan of soup simmering on the petrol stove and night stealing from the forest to engulf the valley. Twenty-nine years after knocking a hole in Helvellyn, this place still draws me. On the other side of the wall the bones of miners still lie in the soil. Up on the mountain, hidden from sight and sound, the waterfall still thunders down its deathly black void.

That???s another thing about obsessions. Once you???ve got one it won???t let go. Or is it the other way round?

For Mark and Eric. May your headlamps burn for ever.

Absolutley fascinating.

1981 – when we still had proper winters clearly.

Thanks for that.

Alen this is a great site,thank you.I have told Janet Arnison about and I am sure between us we can find John Arnison and who know at this stage we might be related to him.did you know there are three branch s to the family.I am sure you know the Arnison s shop in Penrith then thier was the minreal water works,that my branch and the soilcotors in penrith that janets branch,they are related to the drapper shop then thiers the Arnsions who went off to Manchester.sorry about my very serve Dyslexic spelling.

John

Thanks for that, John. Glad to be of any help I can.

Alen, read your booklet and explored the surface remains. Fascinating, beautiful, haunting. Did you ever try to access the no. 2 level portal ? I tried to find all the entrances but only got No. 4 (in the woods) the others are elusive. Pictures herehttps://www.facebook.com/groups/439218202772826/

Hi Mark. I think we had a dig down at No 2 Level very early on but gave up when it became obvious that too much had collapsed. Then when we dug open No 1 Level it didn’t matter, because No 2 can be accessed down the stope. My mate Ian Tyler (of the Keswick Mining Museum) dug open Arnison’s Low Level, so that made three levels open (including No 4 in the woods). We had a crack at No 3 Level, in the side of the beck near the smithy, but that came to nothing.

I haven’t been back there for nearly four years, and everything was covered with scree back then. We put two oil drums in No 2 Level to preserve access, one of which was moved to Arnison’s Low Level. I think you’d have to scrat about a bit to find them.

Hope this is of some use, Alen