TODAY I have a mission. This is no ordinary walk into the Pennine hills. This is a voyage of discovery to a lonely place where ingenious and industrious men built wondrous machines. And ingenious men they certainly were. The Brunels, the Stephensons, Telford and Trevithick might well have hogged industrial revolution glory and claimed immortality. But the unknown men of Green Hurth were no less inventive and ambitious. It’s just that their legacy has all but vanished from the face of the earth . . .

The blue touchpaper for this mission was sparked by an email from Graham Vasey (see his photography blog here), who had read my May 9 post about the old lead mines north-west of Cow Green reservoir, above Teesdale, in particular the long-abandoned Green Hurth Mine. He asked if I’d seen the “giant waterwheel pit”, which I hadn???t.

So I glanced at the satellite view on Bing Maps and there it was, a giant waterwheel pit as viewed from space ??? Cow Green???s answer to the Great Wall of China. What immediately struck me as intriguing was that the waterwheel was not positioned anywhere near the mine workings and their associated machinery. It was hundreds of yards away, at the foot of the moor in the middle of a bog. Why did those ingenious and industrious men build a giant waterwheel pit in the middle of nowhere? I was hooked, I must admit. I had a Miss Marple moment.

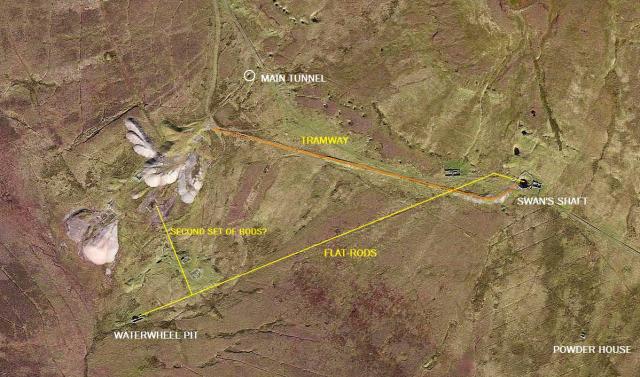

I studied the satellite image. A very faint line of disturbed ground could be discerned running from the waterwheel pit up the fell in the direction of an old shaft, many hundreds of metres away. Was this evidence of an elaborate haulage system or chain of timber “flat-rods” installed to pump water from the shaft? I packed my rucksack ??? not quite feverishly but pretty sharpish. A visit was required. (Click images for high-res versions)

So that was last night. This morning I’m clumping up the track from Cow Green reservoir with a hot sun on the back of my neck. The midges are biting. I knew they would because I left the mosquito repellent at home thinking it would not be needed.

So that was last night. This morning I’m clumping up the track from Cow Green reservoir with a hot sun on the back of my neck. The midges are biting. I knew they would because I left the mosquito repellent at home thinking it would not be needed.

In the meantime I have learned some interesting facts about my destination, courtesy of the Durham Mining Museum website. The mine agent and manager at Green Hurth during the 1890s ??? and about the only name that can be gleaned from history ??? was a Mr J Polglase. That’s a Cornish name, Polglase.

In the meantime I have learned some interesting facts about my destination, courtesy of the Durham Mining Museum website. The mine agent and manager at Green Hurth during the 1890s ??? and about the only name that can be gleaned from history ??? was a Mr J Polglase. That’s a Cornish name, Polglase.

Because of its vast and ancient tin and copper mines, Cornwall was the world’s greatest producer of mining engineers. It was said you could shout down the shaft of any metalliferous mine anywhere in the world and a Cornishman would answer you.

I like stuff like that. It’s history mixed with tradition mixed with folklore. Similarly, it was said you could shout down the engineroom hatch of any ship in the world and a Scottish engineer would respond. We don’t have to look farther than the USS Enterprise to witness this tradition being borne into the future. “Jim. The engines winna take no mair.” Good old Scotty was a projection of an old institution.

Shall we venture into New York police officers all being Irish or shall we leave it at that? Okay. Moving on. But don’t forget, the boys of the NYPD choir weren’t singing Galway Bay for nothing.

Green Hurth Mine, I discovered last night, has been scheduled by English Heritage under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979. A comprehensive archaeological survey is available on the internet. I’m dead chuffed because my theory of the waterwheel being linked to the distant shaft by a series of timber flat-rods has proved correct.

If all this sounds a bit technical and bizarre, do not give up because I’m about to explain this arrangement with words and sketches ??? a bit like John Noakes making a Chieftain tank out of egg boxes and toilet rolls. This really is an ingenious set-up at Green Hurth, so don’t click over to eBay to see how your shares in BAE Systems’ Russian export division are selling.

This building is believed to have been the powder house. It is situated a fair distance from the rest of the mine for safety reasons

It’s a pleasant walk to Green Hurth. I follow a track a couple of miles across undulating moorland with the nascent River Tees sparkling at the foot of the slope and Cross Fell ??? the highest peak in the Pennines ??? standing dark on the horizon. This is one of those places where a person can walk and walk and walk without a care in the world.

It’s a pleasant walk to Green Hurth. I follow a track a couple of miles across undulating moorland with the nascent River Tees sparkling at the foot of the slope and Cross Fell ??? the highest peak in the Pennines ??? standing dark on the horizon. This is one of those places where a person can walk and walk and walk without a care in the world.

It strikes me that the average 19th Century lead miner would not appreciate the grandeur of this location with the same enthusiasm. In this stark environment he lived and toiled with very few comforts and an average life expectancy of about 45 years. The work was cold, wet, hard and dangerous. The pay was poor. The rewards were more of the same to keep his family above the starvation threshold. It was a bit like life under George Osborne only without Cheryl Cole and a continuous stream of major sporting events to deflect attention.

Hot, sweaty, and legs peppered with midge bites I arrive at the first feature, which is the flooded shaft I visited back in May. This is Swan’s Shaft, and it was this shaft that was served by the waterwheel, which was situated out of sight and more than half a kilometre down the fell. The pump, which kept the mine free of water, was situated at the foot of the shaft, 231ft (70.4m) below. So how did the distant waterwheel work the pump?

One of the ruined buildings at Swan???s Shaft has a slot in the wall that has been blocked up. Perhaps a winding cable or machinery belts once passed through it. That???s just a guess, by the way

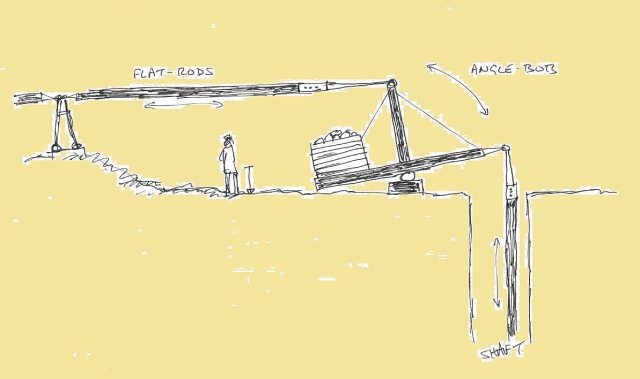

Basically, it was a waterwheel, Jim, but not as we know it (sorry, that’s an Irish doctor not a Scottish or a Cornish engineer). The wheel’s axle had a crank shaft attached to a big lump of timber resembling a roof beam or a ship’s spar. When the crank revolved, the end of the timber fastened to the crank turned in a circular motion, but its free end moved in a reciprocating motion. Got that?

Basically, it was a waterwheel, Jim, but not as we know it (sorry, that’s an Irish doctor not a Scottish or a Cornish engineer). The wheel’s axle had a crank shaft attached to a big lump of timber resembling a roof beam or a ship’s spar. When the crank revolved, the end of the timber fastened to the crank turned in a circular motion, but its free end moved in a reciprocating motion. Got that?

The only analogy I can think of is an old-fashioned sewing machine with the wheel moving the needle up and down. Simple, isn’t it? So the revolving motion of the waterwheel has been transferred to a big lump of wood which is moving backwards and forwards over a distance of, say, a couple of metres.

The only analogy I can think of is an old-fashioned sewing machine with the wheel moving the needle up and down. Simple, isn’t it? So the revolving motion of the waterwheel has been transferred to a big lump of wood which is moving backwards and forwards over a distance of, say, a couple of metres.

Our big lump of wood is called a flat-rod. It is linked to an entire chain of flat-rods that runs up the fell to the shaft. The rods are suspended on pivots and rollers. The end of the last flat-rod sticks out above the top of the shaft. Can you picture it moving backwards and forwards ??? a bloody great unstoppable wooden beam like a giant saw blade? In, out, in out, perhaps ten times a minute. Don’t lean your mountain bike against it, for Christ’s sake.

Here’s more ingenuity ??? how to turn your horizontal reciprocating motion through ninety degrees and transfer it to the pump at the bottom of the shaft. The pump is connected to another series of flat-rods (or pump-rods or spears) that runs the entire 231ft of the shaft and pokes out at the surface. These rods are connected to the waterwheel flat-rods through a device called an angle-bob, which I am not going to attempt to describe. I have drawn a rough picture instead.

So the waterwheel revolves, the flat-rods move backwards and forwards, the angle-bob bobs up and down, the pump-rods slide up and down, the pump mechanism pumps up and down, and countless gallons of oily black water are lifted in stages up a cast-iron pipe (a rising main) and discharged on the surface with a bit of a wet belch.

So the waterwheel revolves, the flat-rods move backwards and forwards, the angle-bob bobs up and down, the pump-rods slide up and down, the pump mechanism pumps up and down, and countless gallons of oily black water are lifted in stages up a cast-iron pipe (a rising main) and discharged on the surface with a bit of a wet belch.

Now the more mechanically-minded reader might be asking himself or herself: “Hang on minute. The weight of all those solid timber rods must be colossal. How on earth does one waterwheel move all that apparatus and lift thousands of gallons of water from a depth of 231ft?”

The weight of the rods is offset with counterbalances. According to the English Heritage survey there were counterbalances located at either end of the?? waterwheel pit. There would also have been a counterbalance on the angle-bob ??? simply a huge box of rocks or scrap metal ??? to offset the pump-rods. In effect, the weight of the timberwork was neutralised. Once it was moving it would have been a bugger to stop.

What an incredible feat of engineering. But my description is over-simplistic. The actual system at Green Hurth was more complex because the flat-rods running up the fellside actually turned a corner before they reached Swan’s Shaft.

And it doesn’t stop there. The English Heritage survey reckons a second set of flat-rods might have sprouted at right-angles from the first set just east of the waterwheel to deliver motion to an ore processing mill. I can’t get my head around this one. It’s just too much on a blazing hot morning. I’ve midges to contend with as well, don’t forget.

And it doesn’t stop there. The English Heritage survey reckons a second set of flat-rods might have sprouted at right-angles from the first set just east of the waterwheel to deliver motion to an ore processing mill. I can’t get my head around this one. It’s just too much on a blazing hot morning. I’ve midges to contend with as well, don’t forget.

There was also a steam engine situated at the top of Swan’s Shaft, possibly for hauling ore from the mine. The engine foundations and anchor bolts are still in situ. Perhaps it replaced the waterwheel at a later date. Or, here’s something intriguing: perhaps the waterwheel superseded the steam engine because that’s exactly what happened a mile or so to the west at Tees Mine.

The Green Hurth waterwheel system is fascinating but not unique. A similar arrangement operated in Red Dell at the head of Coppermines Valley, at Coniston, in the Lake District. Wander up there now and the only visible evidence, other than an impressive waterwheel pit, is a raised causeway that runs up the fellside to Kennel Crag.

This causeway was built for flat-rods. At the top, the rods disappeared into a tunnel and after a few metres arrived at the lip of the Triddle Shaft. There is still an angle-bob complete with its huge box of rocks languishing in the darkness.

SO I’m at the waterwheel pit taking pictures when I receive an edifying lesson in why you shouldn’t poke about these places on your own. I set the camera self-timer, dash onto the walls, trip up and nearly fall headlong into the pit. The wheel had a diameter of about 35ft (10.6m), so I would have had a rough landing.

SO I’m at the waterwheel pit taking pictures when I receive an edifying lesson in why you shouldn’t poke about these places on your own. I set the camera self-timer, dash onto the walls, trip up and nearly fall headlong into the pit. The wheel had a diameter of about 35ft (10.6m), so I would have had a rough landing.

What the hell. Worse things have happened.

There are masses of nettles at Green Hurth Mine. I once read that nettles are a sign of human activity. Men disturb virgin ground and nettles spring up. I have no idea where they come from. But here they are, the only patches of nettles on this vast open moorland. There are nettles in the old powder house, nettles around Swan’s Shaft, nettles growing in the waterwheel pit, and nettles thriving among the ruins of two bothies English Heritage refers to as being “used by the mine manager and the washing master”. There are no dock leaves, by the way.

I leave the waterwheel pit and trudge across the bog to the huge spoil heaps of the main mine. Green Hurth was two mines in one, a bit like those treacle puddings you used to buy in a tin and open both ends. The north mine was Swan’s Shaft. The south mine was worked from a horizontal tunnel. The two were not connected underground but were linked on the surface by a tramway bringing ore down the fell from Swan???s Shaft to be processed.

I leave the waterwheel pit and trudge across the bog to the huge spoil heaps of the main mine. Green Hurth was two mines in one, a bit like those treacle puddings you used to buy in a tin and open both ends. The north mine was Swan’s Shaft. The south mine was worked from a horizontal tunnel. The two were not connected underground but were linked on the surface by a tramway bringing ore down the fell from Swan???s Shaft to be processed.

The processing floors at the main mine are largely undisturbed by time and elements, many of their original wooden features remaining. Of particular interest to me at least are the outlines of two circular buddles. Okay, I’m about worn out through describing stuff like this and I’m sure you’ve reached saturation point. Buddles can wait for another day. Pretty clever stuff though, if you’re into the specific gravity of processed minerals and water separation. Blimey, I bet that’s perked you up.

The processing floors at the main mine are largely undisturbed by time and elements, many of their original wooden features remaining. Of particular interest to me at least are the outlines of two circular buddles. Okay, I’m about worn out through describing stuff like this and I’m sure you’ve reached saturation point. Buddles can wait for another day. Pretty clever stuff though, if you’re into the specific gravity of processed minerals and water separation. Blimey, I bet that’s perked you up.

On the spoil heaps I find evidence that ordinary blokes toiled here ??? the rusty blade of a shovel. My heart goes out to the poor soul who lost it because it was probably deducted from his wages.

On the spoil heaps I find evidence that ordinary blokes toiled here ??? the rusty blade of a shovel. My heart goes out to the poor soul who lost it because it was probably deducted from his wages.

Green Hurth Mine has its origins in 1799, but significant work did not get under way until 1828. Flooding forced the mine’s closure in 1902, by which time it had produced about 18,000 tons of lead. The richest ore also produced 12oz of silver for every ton of lead ??? so if the average was about 9oz per ton we are looking in the region of 9,000lb (4,082kg) of silver produced during the working life of the mine.

Green Hurth Mine has its origins in 1799, but significant work did not get under way until 1828. Flooding forced the mine’s closure in 1902, by which time it had produced about 18,000 tons of lead. The richest ore also produced 12oz of silver for every ton of lead ??? so if the average was about 9oz per ton we are looking in the region of 9,000lb (4,082kg) of silver produced during the working life of the mine.

It dawns on me at this point that every last nail, every sliver of metal and every piece of salvageable timber and slate has been removed from this site. Besides the spoil heaps, the scars on the landscape, the tumbled walls and the nettles, there is nothing here. Everything of worth has been carted away and either recycled or sold.

I return to the car park in the hot afternoon sun. The midges are still biting. At Cow Green reservoir people are relaxing in deck chairs and admiring the Pennine views. It’s a far cry from the days when Mr Polglase trudged along here or trotted past on his horse. Or those unrecorded Victorian engineers watched wagonload after wagonload of flat-rod timber roll along the track; and cast-iron sections of waterwheel; and ponderous crank shafts; and steam engine parts; and boilers; and tub metal and rails; and countless loads of coal. How times change. How the big wheel turns.

So that’s Green Hurth Mine. Like most Pennine lead mines it’s nothing more than a few humps in the heather, a scattering of spoil and old walls. And like most Pennine lead mines, it’s a forgotten monument to British ingenuity, determination, and engineering at its absolute finest.

- To read the full English Heritage report into Green Hurth Mine click here.

- Information on Green Hurth Mine on the Durham Mining Museum website.

- Teesside Mining Company worked Tees Mine and Metalband Mine, which were about a mile from Green Hurth. For an insight in the haphazard life of a Pennine lead mine, read NA Chapman’s Teesside Mining Company, published by the Northern Mine Research Society in 1991.

- Fancy a glance at some excellent pictures of the waterwheel and flat-rod arrangement at Cwm Ciprwth Mine in Wales? Click here.

A great article about a beautiful part of the country. Many thanks for writing it.

Hi Alastair old pal. You are up bright and early.

Cheers, Alen

Could the steam engine have been used if / when there was no waterpower available in the summer months?

That’s an option I suppose because there is very little water up there at the moment. It’s hard to see where the water supply came from. The only running water issues from the drainage level about 100m from the wheel, and that’s only a trickle.

Alen

Another great article Alen! You certainly find some wonderful stories under your feet. When’s that book coming out?

Hi Ash, funnily enough I’ve been giving thought to a book now that I am a man of leisure (that’s if painting, decorating, cooking and other household chores are included in leisure).

Cheers, Alen

A really fascinating article as always, Alen. I didn’t know of this mine…now I will have to take a trip to see it! It’s really intriguing from your excellent photos. I think the engineers at mines like this were the unsung heroes, apart from the poor guys who slaved away underground. The blacksmith at Rhosydd Slate Mine invented an ingenious load handling system which would have been the envy of Brunel and co., yet there’s no evidence that he was paid any more than anyone else in the mine. Incidentally, I looked up the mine on AditNow, but there’s no record of it, could it be known by another name? Your mention of a near-fatal slip reminded me of an occasion when I slipped outside a mine high above Blaenau Ffestiniog. I hung on for some minutes clutching a root of heather until I could get a foothold. All the time an ice cream van was playing Eidelweiss on it’s chimes below…despite being near to a gruesome finale, I had to laugh at the irony of it!

Hi Iain. That’s a great tale about your near-fatal slip. I can think of a few good tunes to die to but Eidelweiss is not one of them.

Yes, the engineers were geniuses. It’s sad to think that most of their achievements were dismantled and scrapped or left underground where few can see them. I’m familiar with Rhosydd. I did a lot of poking about there in the 1980s. I also have some slides somewhere of the Cwm Ciprwth waterwheel, which I took about the same time, but I don’t recall the flat-rods at all.

I don’t think there’s any mention of Green Hurth on the Aditnow website. I haven’t seen an alternative name, though I have seen it referred to as Green Earth somewhere. Can’t remember. According to English Heritage, pictures of the waterwheel and steam engine exist and have been published, but I don’t think they’ve made it to the internet because I’ve searched high and low for them without any luck.

All the best, Alen

Very good, Danny. I feel Tina Turner always has something appropriate to say about every issue.

That was a fascinating post Alen. I have been up there several times over the years and while I knew of the shaft up by the track, the washing floors/crushing area and the water wheel pit lower down, I had little idea how the mine operated.

Nearest theorising I came to was the water pumped out of the shaft at the top would run down the hill on some kind of water way to turn the water wheel. The wheel simply being used to run the machinery at the washing floors. It never occurred to me it was linked to the shaft in another other way, so thanks for that.

Just out of interest, there is also another mine (with spoil heaps as opposed to just a level) near this one about half a kilometre away right next to the Tees at Smithy Sike. Is this also part of the Swan Shaft/Green Hurth mine complex as well do you think?

Hi David. Yes, it’s a fascinating place. I’d love to go back about 150 years an see what these places looked like. Teesdale and Weardale would have borne no resemblance to today. These quiet rural valleys would have been filthy industrial centres full of smoke and noise.

I haven’t a clue about the mine at Smithy Sike. When mining companies took out leases they were given the right to a “sett”, which was a legally-defined area of ground. The Tees Mine and Metalband Mine, both beneath Bellbeaver Rigg, were part of a neighbouring sett, so Smithy Sike was almost certainly part of the Green Hurth sett and worked by the same company. I never had a snoop round Smithy Sike so I can feel another walk coming on.

Cheers, Alen

Another fascinating post cuz, although it must be said that James Doohan (Canadian of Irish descent) had the worst Scottish accent in the history of the universe. That being said the town I used to live in, Linlithgow, has probably the only premorial in the world to mark Scotty’s birth in 2222!

Ha ha. You’ll be telling me next that Leonard Nimoy wasn’t actually from Vulcan. Poor old Scotty. At least his accent was marginally better than Dick van Dyke’s in Mary Poppins.

Cheers now kinsman, Alen

Fascinating one. Had to look up buddle as you are playing suspense games. And beautiful photos as always. I’m glad you didn’t take your header, by the way!

Buddles, kibbles, tulleys, corracks . . . . the list is almost endless. An untapped wealth of abandoned words. That’s given me an idea for a post, Mrs P.

Cheers, Alen

Great post, anything to do with the old lead mines gets my attention. This was beautifully written and the explanation was easy to understand. I must get up there one day…looks a superb place to explore.

Hi James. It’s great walking country and not as popular with the crowds as it might be. My recent visit was midweek and I passed only one person in the whole day.

All the best, Alen

Off the beaten track, eh? Away from the crowds..Just the way I like it :-)

Another great post,thank you.

Hiya John. Good to hear from you.

Cheers, Alen

Hi Alen, I enjoyed this, although I can’t pretend to fully understand the workings of the wheel. The work involved in constructing all that, and putting it in place, must have been colossal – and you wonder how many lives were lost with so many hazards. I’m transfixed by that piece of quartz, and I’m also glad that you didn’t come a cropper in that pit! It’s easy to appreciate the lives of people in centuries past if you can see old mills and factories, but with mines it’s like a forgotten history, and the added problem is that the mechanical aspects aren’t easily appreciated by most people – so it takes someone passionate about it, like yourself, to fire their interest.

Hi Jo. That’s an interesting aspect you’ve raised there. It’s one thing to design mechanisms such as these, but it’s quite another to get all the equipment to a remote moorland location and actually build them. The skill that went into the construction work alone is to be marveled at.

I’m glad you like the quartz. I wasn’t sure what it was, which is why I didn’t put a caption on the picture. I’m not up on my minerals.

Cheers, Alen

Perhaps, as David says the water pumped up from the shaft ran down a trough that powered the waterwheel. The ingenious part being that the waterwheel powered the pump that drew water up the shaft. Did these 19th century miners create perpetual motion?

Cracking read that. Thanks.

Ha ha. I once read a book on self-sufficiency by John Seymour in which he said anyone who relies on the previous year’s vegetable compost to sustain their vegetable patch is trying to lift themselves off the ground by their own boot-laces. It doesn’t work. Likewise the idea of perpetual motion, although it would have been the mine-owner’s dream.

David’s notion was that the pump water powered the mill. But I like the idea of the water pumping itself out of the mine. Even Brunel and Telford couldn’t have made that one work!

Cheers, Alen

Alen, I did not mean that the water from the shaft was the sole source of power. I had assumed power from another source (the engine mount near the shaft I assumed was the actual pump using steam) This being used to pump water from the shaft and it was this water that would run down to the wheel and drive the machinery lower down. Clearly wrong of course, but I never even heard of flat rods.

Hi David. No, I knew what you meant. That the water from the shaft powered the machinery at the mill, and the waterwheel had nothing to do with the shaft.

I think Jonjo either misread your comment or was perhaps being a little bit mischievous.

All the best, Alen

It is an interesting story, Alen. My favorite thing about hiking is if you are motivated by an investigative work. It must have been exciting to involve aerial photographs.

Thanks for your teaching patriotism. Your photos are really great and your drawings are nice and illustrative.

I’m glad you did not fall into the pit even if worse things have happened according to your own statement :-)

I don’t hope you got any midges in the optics. Those bugs can pass through the most fine mosquito net.

All the best,

Hanna

Hej Hanna. Thanks for your comment, as always. I love a bit of investigative work like this. I’ve been been poking about in old mines and writing articles about them for years ??? decades even. I really enjoy the work because it stretches the mind in new and different directions.

I’m glad I didn’t fall in the pit as well. I would probably still be up there waiting to be found. No mobile phone reception up there.

Cheers, Alen

Please stop that scenario I don’t need the big brush :-)

Take care,

Hanna

Fantastic post Alen, and thanks for the link!! Tell you what though your a braver man then me standing on the side of that pit, just looking into that pit from the side gave me the willies!! haha

Hiya Graham. Thank you for the information. I spent a very pleasant day up there and thoroughly enjoyed myself.

Cheers, Alen

Fascinating: I see from the map that there is a place at Cow Green mine called the Rods: I

wonder if there was something similar there?

Below Green Hurth there is a mining area called Slunks: shades of the Dalton Slunks Club

for anarchic drinkers? Probably not.

Hi Jonathan. I missed that place called the Rods. When you look at the satellite image the entire hillside has been scarred by workings. Oh to go back a hundred years or so and have a poke about ??? and a few pints in the Langdon Beck bar.

I like the Slunks theory as well. In Devonshire Dock there was an electricians’ workshop known as Cripple Creek where the old-timers were sent for an easy life when they reached a certain age. Needless to say I never worked there. But the name stuck. So you might be on to something there.

Cheers, Alen

PS Great party as usual. Thanks.

Great post , great pictures. I love looking at the remains of old industry, good one :-)

Hi Wessyman. Thanks for that.

Alen

Hello Alen,

A picture of the wheel at Green Hurth can be seen on this page:

http://www.aditnow.co.uk/photo/Greenhurth-Lead-Mine-Archive-Album-Image-52962/

If you haven’t seen it before, the Adit Now website will keep you occupied for a day or three – there is lots of interest within.

Very much enjoying your “rambles” both physically and with the keyboard, a visit to your site will probably become a regular thing. Many thanks.

Cheers

Alan

Hi Alan. Thank you very much for that. What an incredible picture. I haven’t come across it before. Everything is on there, including the manager’s house in the background, the balance bob, the rods, just about everything.

Cheers, now, Alen

An extract from that photo appears towards the front of “The mines & minerals of Teesdale & Weardale” by K.W. Sedman, published by the Cleveland County Museum Service. Acknowlegement is given to Beamish for the use of photos from their collection. I wonder what rights “rodel” claims to have?

http://collections.beamish.org.uk/search-results?query=greenhurth&go.x=18&go.y=26&searchType=archive

Interesting point, Alastair. My understanding of the copyright laws is that all rights belong to the photographer or his or her estate up until the 50th anniversary of their death. Ownership of an image does not necessarily imply copyright.

The laws altered recently so I might be wrong.

Alen

I think you are probably right. For interest, the mine shut in 1902.